You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

History Questions Not Worth Their Own Thread VII

- Thread starter Plotinus

- Start date

James Stuart

King

Yep. Germany wanted to direct the Pact against the USSR, which it saw as an existential threat, but which Japan saw as a threat to northwestern expansion, but not really as a threat to itself or its empire. Japan was interested in directing it against Britain, which it saw as a threat to its overseas empire and naval pre-eminence. Deterring the US was simply a nice bonus.Which incidentally is exactly what happened. Funny old world.

This is perhaps the classic example of two parties in an alliance having cross-purposes when signing it; it's mentioned in most books on the topic. While we're on the topic, Italy was mostly interested in using the Pact against France, so you have your three main signatories all signing with completely different reasoning.

ParkCungHee

Deity

- Joined

- Aug 13, 2006

- Messages

- 12,921

I'll also point out that the switch from the RoC to Japan was also a classic case of Nazi economic mismanagement.

Germany had many natural reasons to want warm relations with a stable and defensible China. Germany was the one power who's intentions in the Far East the Chinese could trust, and could therefor allow economic concessions to without fear of gunboats arriving.

The Germans, suffering from a flagging economy but with a tremendous manufacturing base, had a lot to hope for out of the millions of potential customers the Chinese represented.

Germany had many natural reasons to want warm relations with a stable and defensible China. Germany was the one power who's intentions in the Far East the Chinese could trust, and could therefor allow economic concessions to without fear of gunboats arriving.

The Germans, suffering from a flagging economy but with a tremendous manufacturing base, had a lot to hope for out of the millions of potential customers the Chinese represented.

James Stuart

King

You want typical Nazi economic mismanagement, combined with typical Ribbentrop foreign policy stupidity? Look no further than the fact that Germany got literally half its tungsten from China, yet unilaterally stopped trading with the latter in 1938. Goering was especially irate at the fact that as the head of the Four Year Plan, it was his job to tell German industrialists to stop trading with the country's third-largest trading partner for a vital substance. He apparently threatened to have Ribbentrop "have an accident on the autobahn."I'll also point out that the switch from the RoC to Japan was also a classic case of Nazi economic mismanagement.

Germany had many natural reasons to want warm relations with a stable and defensible China. Germany was the one power who's intentions in the Far East the Chinese could trust, and could therefor allow economic concessions to without fear of gunboats arriving.

The Germans, suffering from a flagging economy but with a tremendous manufacturing base, had a lot to hope for out of the millions of potential customers the Chinese represented.

This came three months before Ribbentrop destroyed German relations with Poland, literally Hitler's personal foreign policy project for five years. The man may have been the least competent person the Nazi's had in government, which is like saying that someone is less mobile than a corpse.

This came three months before Ribbentrop destroyed German relations with Poland, literally Hitler's personal foreign policy project for five years.

I'm sure the 1939 invasion of Poland was Hitler's idea of restoring relations with his 'pet project'...

James Stuart

King

Do you know anything at all about German-Polish foreign relations in the 1930s? Or is this your usual "I don't know a thing about the topic, but still feel qualified to discuss it" moment?I'm sure the 1939 invasion of Poland was Hitler's idea of restoring relations with his 'pet project'...

JohannaK

Heroically Clueless

Now, that is a subject I never heard about. Which was the state of relations between Poland and Nazi Germany in the interwar period and how did they evolve under the Nazi regime until the outbreak of WW2?

James Stuart

King

Under the Weimar Republic, German-Polish relations were in a state of flux. Germany would seek to play Lithuania and Poland off against one another, alternately supporting one, then the other, in the hope of keeping both too pre-occupied to interfere in East Prussia. Eventually, however, the situation with Poland became problematic enough that Germany, in an attempt to win political and territorial concessions, instituted a customs war with its neighbour. This raised tariffs on Poland's primary export, coal, having a deleterious effect on the Polish economy. Poland retaliated by raising tariffs on German goods, but Germany had by far the stronger economy, with a diversified export market that was strong enough to scupper a large proposed British loan to Poland.Now, that is a subject I never heard about. Which was the state of relations between Poland and Nazi Germany in the interwar period and how did they evolve under the Nazi regime until the outbreak of WW2?

Poland sought defence from Germany, and therefore formed a close alliance with France. Germany responded with a secret military agreement with the USSR. French diplomacy in the immediate post-war period was designed to keep Germany weak through the use of multilateral and bilateral defence treaties, such as the Little Entente. The mood in France became more and more pacifistic, however, and led directly to the Locarno Treaty with Germany.

There were many aspects to this treaty, including a debt-cancellation deal with Poland, but the issue of primary importance to both the French and Polish governments - and the German one - was the ratification of the territorial rearrangements in the Treaty of Versailles. That is, Germany agreed to recognise, and not attempt to regain, the territory it lost at the end of WWI... In the west. In the east and north, Germany was given a free hand. France did not demand, much to Poland's disgust, that Germany recognise the borders with Poland, Lithuania, Denmark, and Czechoslovakia. This opened up the distinct possibility that Germany may seek to make good on revanchist claims on those states in the future, and that France might let them.

This treaty, while securing France from a then non-existent German threat, did so at the expense of cutting loose all of France's allies in Eastern Europe, especially Poland. The Poles, rightly furious, sought their security by pursuing a closer relationship with Germany, recognising that the divided state was both less threatening than, and more likely to cause problems, than the USSR. By this time, however, the Weimar Republic was suffering from the collapse of the investment bubble brought about by the Great Depression. So the Poles were forced to stay pro-French by the lack of options. Weimar was also in a state of constant political flux, with the very real threat of a military coup or communist takeover.

Enter Hitler. Hitler was appointed Chancellor on 30 January, 1933, and immediately took a different foreign policy approach. The previous Weimar cooperation with the USSR was abandoned, freeing Poland from fear of a two-front war between with the two pariah states. Hitler saw his primary foreign and domestic policy initiative as defending Germany from communism; this image of an anti-communist strongman was why the nationalists had called him to power in the first place. As such, the USSR was the most obvious external threat, and the KPD the most prominent internal one. Hitler's anti-communism and anti-Semitism was very attractive to Second Commonwealth, itself a very anti-communist and anti-Semitic state. The Camp of National Unity didn't take charge until 1937, but previous governments were almost as authoritarian; like Hitler, Mussolini was their model.

This new ideological similarity, and the change in Germany's stance towards the USSR, opened up the possibility of a rapprochement between the two powers. Hitler saw Poland as both a buffer to, and potential springboard and ally for an assault on, the USSR. He almost immediately began peppering his speeches with pro-Polish comments, even though he'd gladly used anti-Polonism to win support in Prussia and Bavaraia before he came to power (for the record, these are bloody hard to find online, at least for an English-speaker. They're probably a lot easier to find in German).

On the part of Poland, its Foreign Minister Jozef Beck initially sort to fulfill dictator Jozef Pilsudski's dream of an Eastern European coalition against both Germany and the USSR. He quickly, however, recognised that this was an untenable position, and signed a Non-Aggression Pact with Germany in 1934. Beck did resist Nazi attempts, however, to enlist Poland in an anti-USSR alliance, pursued by both Hitler and his moderate nationalist Reich Minister of Foreign Affairs, Konstantin von Neurath, due to fear that this would kill off any chance of continued agreements with France and Britain, and possibly precipitate a Soviet reaction.

This policy was pursued diligently by both Hitler and Beck, as well as Pilsudski's successor Kazmierz Bartel from 1933-38. For what it's worth, Pilsudski's death in 1935 may have scuppered a proposal for Polish entry into a proto-Anti-Comintern Pact; Bartel was less interested in the German alliance, preferring to keep both the USSR and Germany at arm's length. This did not stop German attempts to keep Poland onside, however, as it was seen as expedient to keep Poland out of the French orbit, even if it could not be brought into the German one; exemptions in favour of Poles were made in Germany's laws on immigrant labour, Poland was given territory in the Munich Pact, and Hitler and Goebbels kept revanchist claims on Danzig and the Polish Corridor out of German publications, in particular Der Sturmer.

This policy changed after the Munich Pact. Joachim von Ribbentrop, Neurath's useless replacement, who had already destroyed the profitable relationship with China, and taken credit for the anschluss and the Pact despite having both handled by Hermann Goering - prompting Goering to slap him in the face in front of a gleeful Goebbels in September 1938 - asked Poland if it would be willing to renegotiate the status of Danzig. Poland, correctly deducing that this would be economic suicide for Gdynia and their independent foreign trade, balked. So Ribbentrop, instead of politely changing the subject, angrily expelled all Polish Jews from the Sudetenland, an action he had absolutely zero authority to do. Most of these Jews had fled the anti-Semitism of Poland decades before; many of them were born in Czechoslovakia, and didn't speak a word of Polish.

This understandably angered Poland, which refused the Jews entry, leaving them stranded in no-man's-land between the two states; some were even stuck living on an island between the two states for a month. Eventually Poland relented, only to face another angry request from Ribbentrop for a renegotiation of Danzig's status. He was politely told to get stuffed.

Ribbentrop's Anglo-phobia, which had previously kept him out of Hitler's inner circle, had now become an asset; Hitler's exposure to Chamberlain, and the unwanted Munich Pact, had left him in utter contempt of the "little worms," and "umbrella politicians" (the umbrella is a symbol of peace in Germany). Ribbentrop's long history of denouncing everything British was now seen by the Fuhrer as prophetic, rather than embarrassing, and he began to listen to the RAM more. Ribbentrop was already anti-Polish, and Hitler's failures to bring Poland into his orbit, as well as his newfound belief that the British and French were too cowardly to oppose him, led him inexorably towards the anti-Polish stance culminating in the outbreak of WWII.

Hitler's first ever negative opinion of Poland in public as Fuhrer was in March 1939; over six years after he came to power. Even then, several more attempts were made to renegotiate over Danzig before Hitler expelled Polish migrant workers from eastern Germany, with Ribbentrop's backing - and over protests from Robert Ley and Richard Walther Darre, who recognised their necessity to German agriculture - precipitating both an economic and diplomatic crisis. Eventually, as we all know, German and Polish relations descended enough for war to break out.

JohannaK

Heroically Clueless

That was a very enlightening and helpful post, James Stuart. Thanks.

ParkCungHee

Deity

- Joined

- Aug 13, 2006

- Messages

- 12,921

The thing that's most mind-boggling is the Ribbentrop was the only Nazi that was in the halls of power before he joined the Nazi Party. Can't blame all of Germany's stupid on them, I guess.You want typical Nazi economic mismanagement, combined with typical Ribbentrop foreign policy stupidity? Look no further than the fact that Germany got literally half its tungsten from China, yet unilaterally stopped trading with the latter in 1938. Goering was especially irate at the fact that as the head of the Four Year Plan, it was his job to tell German industrialists to stop trading with the country's third-largest trading partner for a vital substance. He apparently threatened to have Ribbentrop "have an accident on the autobahn."

This came three months before Ribbentrop destroyed German relations with Poland, literally Hitler's personal foreign policy project for five years. The man may have been the least competent person the Nazi's had in government, which is like saying that someone is less mobile than a corpse.

JohannaK

Heroically Clueless

So Ribbentrop is the Nazi every other Nazi hated. As well as almost every other person he met.

Now, I wonder what was the population of London before and after the Great Fire in the 1660s?

How did the city evolve, demographically and urbanistically, from then to the end of the 19th Century?

Now, I wonder what was the population of London before and after the Great Fire in the 1660s?

How did the city evolve, demographically and urbanistically, from then to the end of the 19th Century?

sophie

Break My Heart

So Ribbentrop is the Nazi every other Nazi hated. As well as almost every other person he met.

Now, I wonder what was the population of London before and after the Great Fire in the 1660s?

What did the city evolve, demographically and urbanistically, from then to the end of the 19th Century?

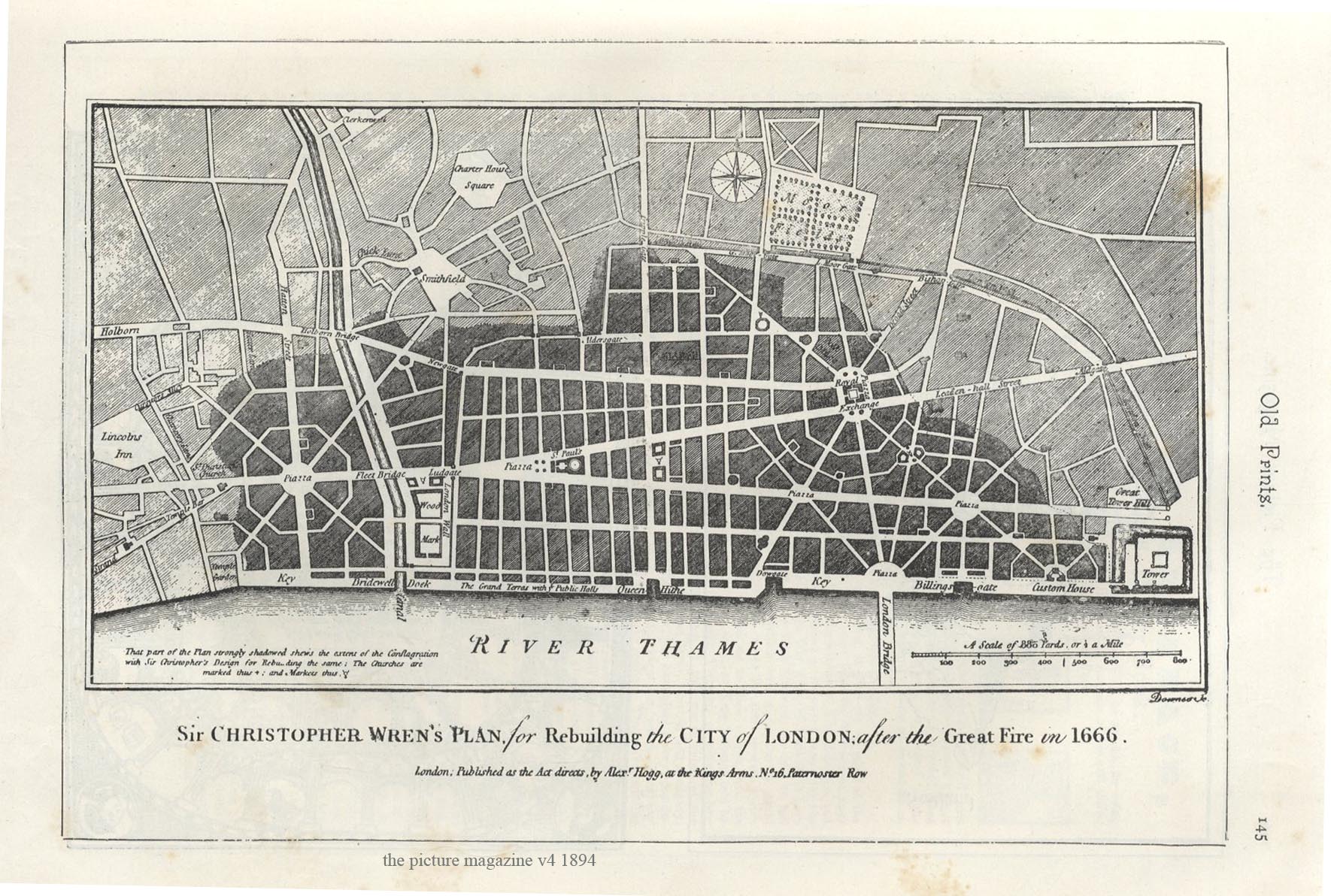

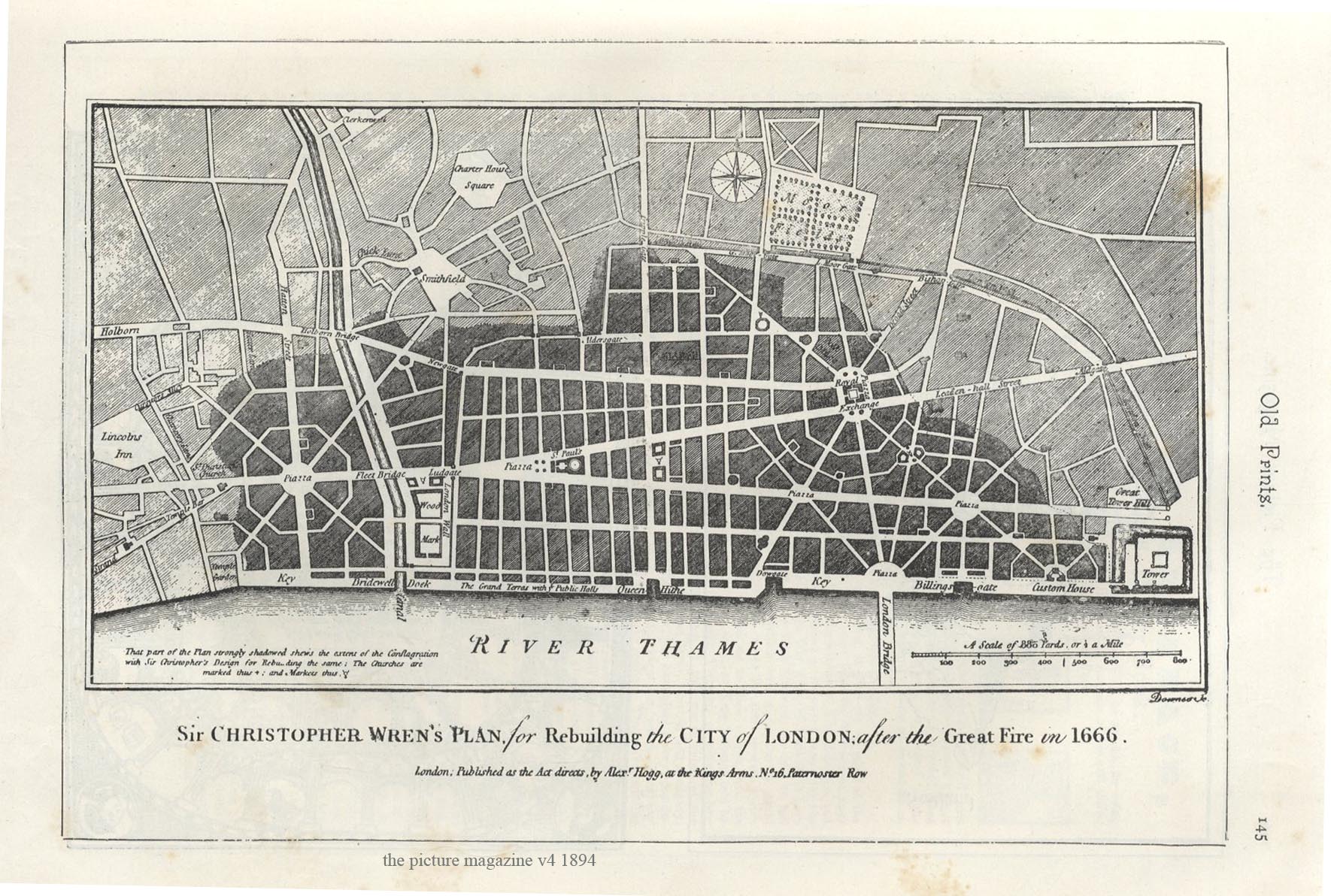

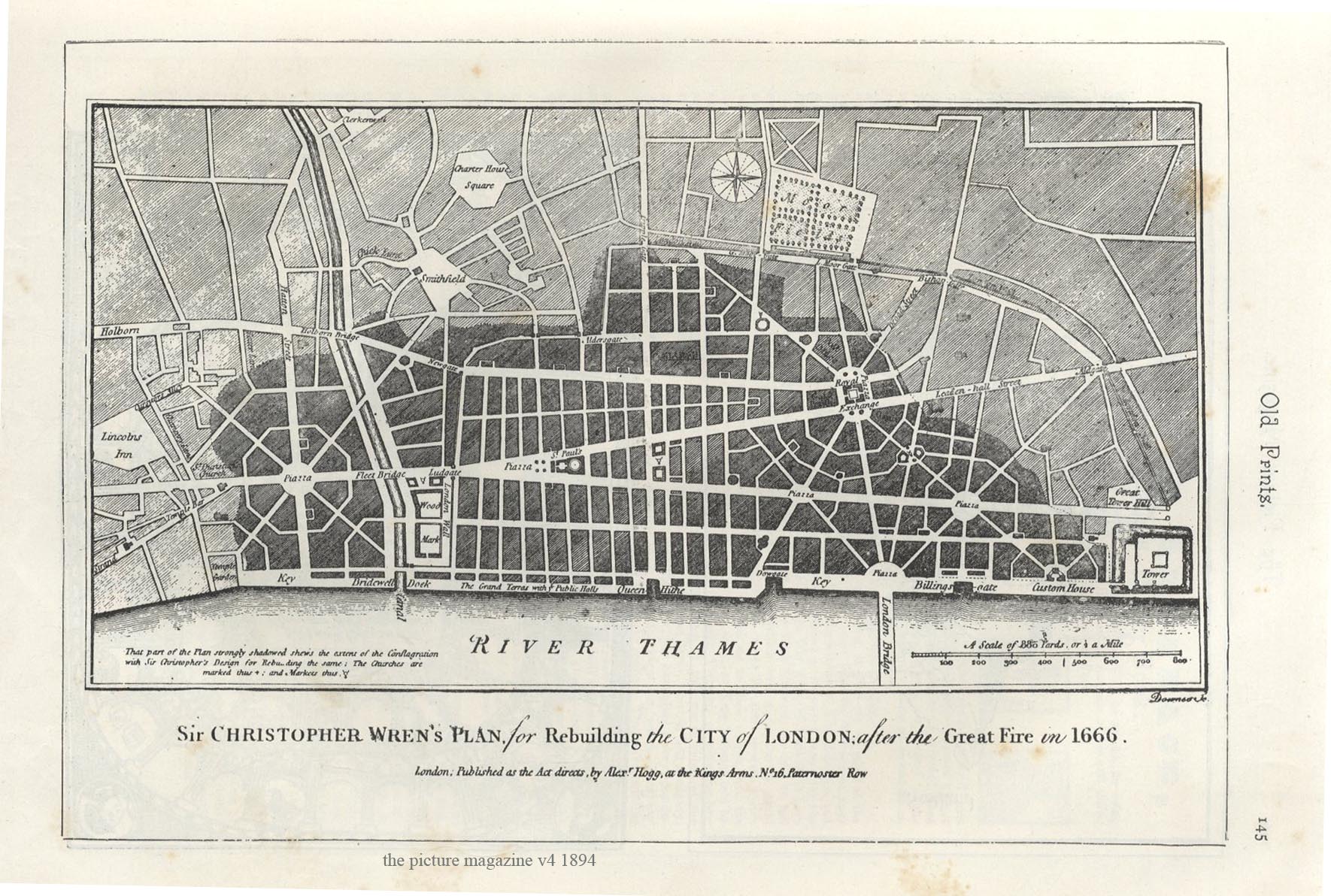

1) The fire enabled planners to come back and redo the street layout in a (semi-)sensible manner

2) Christopher Wren was in charge of rebuilding many of the destroyed churches.

JohannaK

Heroically Clueless

The one helpful thing about your post is that it pointed out my typo. What is supposed to be this semi-sensible manner? Who is Christopher Wren and why should I care about the churches?

sophie

Break My Heart

The one helpful thing about your post is that it pointed out my typo. What is supposed to be this semi-sensible manner? Who is Christopher Wren and why should I care about the churches?

London's most famous architect:

Spoiler :

Seriously? You could solve not knowing about Sir Christopher Wren with a simple internet search.Who is Christopher Wren and why should I care about the churches?

sophie

Break My Heart

Also I misremembered the part about the streets being redesigned. King's and Queen's streets were the only substantial part of the city plan itself that changed. The City originally wanted the design of London to be totally reworked, with the confusing alleys and sidestreets torn down and replaced with a more sensible Italian design of straight(ish) roads and piazzas. They also wanted all of the buildings to be rebuilt in stone. London at the time, like pretty much all cities at that point, was comprised mostly of wooden buildings haphazardly thrown up wherever open space was available (hence the horrific destructive fire). Wren proposed making the streets be not convoluted and crappy, but the proposal was rejected for being too expensive and complicated to resolve. Rebuilding the churches, particularly his masterstroke in St. Pauls (perhaps the 3rd or 4th most recognizable church in the world) took the rest of his life. IIRC he didn't live to see St. Pauls finished.

Wren was responsible for rebuilding most of the churches destroyed in the fire. Many of them were redesigned entirely.

The most famous are the two I showed above, St. Paul's (which was given the largest dome every attempted at the time), and St. Bride's, whose design supposedly was the inspiration for the tiered wedding cakes that have become commonplace at weddings today.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Christopher_Wren_churches_in_London

Spoiler :

Wren was responsible for rebuilding most of the churches destroyed in the fire. Many of them were redesigned entirely.

The most famous are the two I showed above, St. Paul's (which was given the largest dome every attempted at the time), and St. Bride's, whose design supposedly was the inspiration for the tiered wedding cakes that have become commonplace at weddings today.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Christopher_Wren_churches_in_London

JohannaK

Heroically Clueless

I could imagine that Wren was the St Paul architect, but my point was that the post hardly addressed my questions or did so insufficiently. Of course, though, I don't have a right to expect a decently elaborate answer.

James Stuart

King

There were other Nazis in positions of power prior to their, uh, Nazi-hood. Keitel immediately comes to mind. Ribbentrop probably wasn't even the most powerful; I think I just mentioned the most powerful, but Goebbels and Streicher both owned popular newspapers before they joined the Party, the aforementioned Neurath didn't join the Party until 1937, as it was seen as useful to have the Foreign Minister be a non-Nazi nationalist, and Helldorf was a ranking officer in the police force and on the verge of becoming State Chancellor of Prussia before joining the Party in March 1933. Helldorf ran the Gestapo, so he may have been more powerful than Keitel or Ribbentrop.The thing that's most mind-boggling is the Ribbentrop was the only Nazi that was in the halls of power before he joined the Nazi Party. Can't blame all of Germany's stupid on them, I guess.

@JoanK: No one liked Ribbentrop, not even his own wife. She was suspected of affairs with several high-ranking Nazis. Goering almost certainly shtupped her, just to have something over Ribbentrop.

Also I misremembered the part about the streets being redesigned. King's and Queen's streets were the only substantial part of the city plan itself that changed. The City originally wanted the design of London to be totally reworked, with the confusing alleys and sidestreets torn down and replaced with a more sensible Italian design of straight(ish) roads and piazzas. They also wanted all of the buildings to be rebuilt in stone. London at the time, like pretty much all cities at that point, was comprised mostly of wooden buildings haphazardly thrown up wherever open space was available (hence the horrific destructive fire). Wren proposed making the streets be not convoluted and crappy, but the proposal was rejected for being too expensive and complicated to resolve. Rebuilding the churches, particularly his masterstroke in St. Pauls (perhaps the 3rd or 4th most recognizable church in the world) took the rest of his life. IIRC he didn't live to see St. Pauls finished.

Spoiler :

Wren was responsible for rebuilding most of the churches destroyed in the fire. Many of them were redesigned entirely.

The most famous are the two I showed above, St. Paul's (which was given the largest dome every attempted at the time), and St. Bride's, whose design supposedly was the inspiration for the tiered wedding cakes that have become commonplace at weddings today.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Christopher_Wren_churches_in_London

From walking around London, most of the stone buildings which make up the centre are from about the time of Trafalgar or later. I think the grand phase of architecture was from somewhere between 1805 and 1914, and generally financed by the profits of imperial expansion and motivated by the need to show them off. It's quite remarkable how many London landmarks have the names of far-off places written on them to commemorate an invasion or a war.

As for Nazis, the German establishment in the late thirties and early forties didn't come out of the blue, especially in organisations like the armed forces. The people leading the armies into Poland had served for many years; in a sense, that probably explains why the army and navy proved much more conservative and difficult for Hitler to deal with than the air force, which was entirely built by the Nazis themselves.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 14

- Views

- 2K

- Replies

- 253

- Views

- 19K

- Replies

- 0

- Views

- 5K