You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Money. Doing it Right this Time.

- Thread starter Cutlass

- Start date

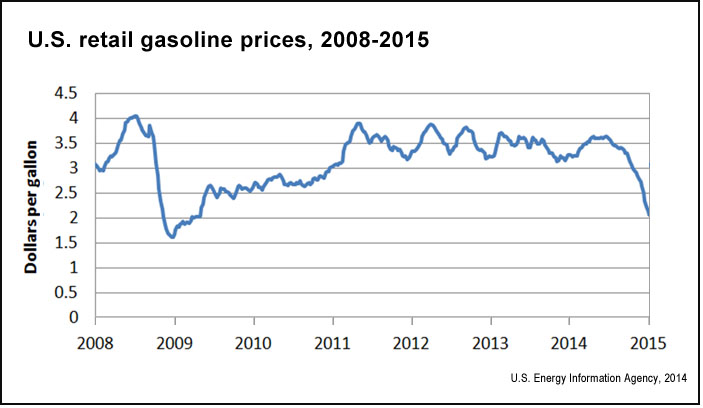

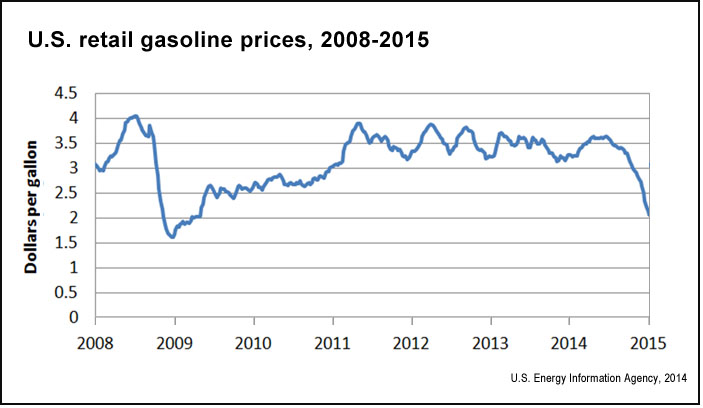

Production is up in many areas. And consumption is still depressed in many areas due to weak economic performance.

As you can see, oil prices are far down now from where they have been in the recent past. Gasoline prices more or less reflect that change. But they don't do so perfectly. And that's a measure of the imperfections of the domestic refining and distributing market. You were paying more for gas last year.

As you can see, oil prices are far down now from where they have been in the recent past. Gasoline prices more or less reflect that change. But they don't do so perfectly. And that's a measure of the imperfections of the domestic refining and distributing market. You were paying more for gas last year.

Hygro

soundcloud.com/hygro/

Back on the balanced budgets question I'm afraid - I think by now I understand the theory explaining why not balanced budgets (especially for a country that prints the currency it borrows in) are much better than balanced ones. So where does this sort of thing come from? The IMF aren't even France or Germany, who would have an incentive to point to Britain as an austerity 'success story' so as to encourage the likes of Greece and Italy to copy them and save French and German money.

EDIT: Whoops - duly fixed, thanks El Mac.

Mainland European economists very frequently suck. In her case (IMF chief), she's a lawyer.

(so is the CEO of Goldman Sachs btw).

The major problem over the years with the IMF (and the World Bank), which were created to help the world develop and become prosperous, is that they are, ultimately, run by bankers. And the first priority of bankers is to get repaid.

Regardless of the consequences to the debtor.

And because of this the IMF has a long tradition of demanding policies on the part of the debtors which are harmful both in the near term and the long term to the futures of those countries, and the people in them. What you are seeing is a conflict of interest. Instead of acting as a development agency, the IMF too much acts as a bank. And a particularly nasty bank at that. And they have a research arm. And so their own research tells them that they do more harm then good. But they do it anyways, because ultimately the bankers are running the show.

I think you're too easy on the purposes for the IMF/WB's creation. They were created as part of an imperial infrastructure, same with the strengthening of the Bundesbank/ECB in Europe and the the monetary mechanisms in West Africa run by the French.

Sorry, just really wanted to post in the money thread

great work as usual guys

great work as usual guysYes, Azale, but not even the French's (post?-)imperial banks are as savage as the IMF. Incidentally, the rape of the Balkans perpetrated by 'mainland' Europe is already running by leaps and bounds to classic IMF-style pillage.

Katie Boundary

Chieftain

- Joined

- Apr 20, 2015

- Messages

- 14

Fiat currency is fine as long as you keep its value stable over time instead of debasing it. The Romans tried debasing the Aureus (a gold coin) over a long period of time and it didn't end well.

Given that Roman currency was never worth anything close to its metal value, it's more complicated than that. Sometimes debasement is a good policy.

Lohrenswald

世界的 bottom ranked physicist

How so? Does it have to do with commodities and services being available in different amounts at different times? Or is it related to banking in any way?

(Sorry if I sound stupid)

(Sorry if I sound stupid)

Tahuti

Writing Deity

- Joined

- Nov 17, 2005

- Messages

- 9,492

A currency with a completely stable value over time will ruin the economy it is supposed to support. So that idea is out.

For a debt-based economy, lack of inflation causes pain for certain.

How so? Does it have to do with commodities and services being available in different amounts at different times? Or is it related to banking in any way?

(Sorry if I sound stupid)

To a large extent, it has to do with banking: Theoretically, creditors thrive on deflation so they can reap even bigger profits. They also lose on inflation, theoretically, since less is repaid and debtors get away with that completely.

The reason why is this is always theoretically so and never in practice is because deflation makes repaying debts hard. The risks for debt default become unacceptable and eventually, most creditors lose out, debtors fail to repay their debts and the economy collapses if this process is left unchecked.

A currency with a completely stable value over time will ruin the economy it is supposed to support. So that idea is out.

Well, depends what we mean by 'completely stable'. We prefer an inflation rate slightly higher than zero for fairly good reasons (higher productivity, mainly). But an inflation rate that perfectly tracked the growth rate wouldn't be so bad. If you could buy a 'modern car' for $20k or a 'modern TV' for $350 in 2030, it wouldn't matter much. I'm not sure what the increased productivity from having a 2% inflation rate is, it's mostly the 'we didn't go into deflation' that matters.

The Romans had a negligible growth rate (in factors we're counting these days).

Katie Boundary

Chieftain

- Joined

- Apr 20, 2015

- Messages

- 14

(Sorry if I sound stupid)

Everyone sounds stupid to someone else whenever they say something that someone else disagrees with

To a large extent, it has to do with banking: Theoretically, creditors thrive on deflation so they can reap even bigger profits. They also lose on inflation, theoretically, since less is repaid and debtors get away with that completely.

The reason why is this is always theoretically so and never in practice is because deflation makes repaying debts hard. The risks for debt default become unacceptable and eventually, most creditors lose out, debtors fail to repay their debts and the economy collapses if this process is left unchecked.

This only holds true if inflation is unpredictable. If banks know that inflation will be x% over the next y years, then interest rates will be adjusted accordingly and nothing will really change.

Well, depends what we mean by 'completely stable'.

The value of currency can never be "completely" stable because value is relative. We can, however, ensure that its value is stable over time within a certain margin of error for the same reasons why we can guarantee 2% inflation per year within a certain margin of error.

How so? Does it have to do with commodities and services being available in different amounts at different times? Or is it related to banking in any way?

(Sorry if I sound stupid)

When the central bank gets the money supply wrong, the economy is disrupted. When money is too tight, people lose their jobs, businesses close, many bad things happen.

For a debt-based economy, lack of inflation causes pain for certain.

To a large extent, it has to do with banking: Theoretically, creditors thrive on deflation so they can reap even bigger profits. They also lose on inflation, theoretically, since less is repaid and debtors get away with that completely.

The reason why is this is always theoretically so and never in practice is because deflation makes repaying debts hard. The risks for debt default become unacceptable and eventually, most creditors lose out, debtors fail to repay their debts and the economy collapses if this process is left unchecked.

If the inflation is stable, then creditors don't lose from inflation. They price it in in advance.

Well, depends what we mean by 'completely stable'. We prefer an inflation rate slightly higher than zero for fairly good reasons (higher productivity, mainly). But an inflation rate that perfectly tracked the growth rate wouldn't be so bad. If you could buy a 'modern car' for $20k or a 'modern TV' for $350 in 2030, it wouldn't matter much. I'm not sure what the increased productivity from having a 2% inflation rate is, it's mostly the 'we didn't go into deflation' that matters.

The problem there is that we're in an economy where millions of different things are traded every day. And the prices of those millions of things change at different rates, and for different reasons. It's too complex for the certainty of knowing that any program could exactly hit any target of perfectly stable prices.

onejayhawk

Afflicted with reason

If the inflation is stable, then creditors don't lose from inflation. They price it in in advance.

This si true of a lot more than inflation. Regulations, enforcement of same and taxes are three big ones.

J

The problem there is that we're in an economy where millions of different things are traded every day. And the prices of those millions of things change at different rates, and for different reasons. It's too complex for the certainty of knowing that any program could exactly hit any target of perfectly stable prices.

Oh, it can't be done exactly. Targeting a slightly above zero inflation rate is really beneficial for a host of reasons. It makes it easier to avoid 'accidentally' getting deflation. You get the small production bump from increased employment. It discourages saving currency, and encourages lending currency, creating a 'feed-forward' effect that prevents accidental deflation.

Its downside is that it punishes low-savvy savers. People will sock money away into a defined-benefits program thinking they're going to be richer in the future than they actually end up being.

This si true of a lot more than inflation. Regulations, enforcement of same and taxes are three big ones.

Very true. In general, predictability is valuable. I'd rather make a house of cards on a stable table. I'm going to put less work into a sandcastle if the tide is coming in, but more if the tide is going out.

I often liken inflation to water. At above freezing, we can conduct trade between towns on opposite sides of a lake. At below freezing, profitable trade is still possible, it's just significantly harder and so there's less growth overall. But if the lake oscillates between freezing and liquid? Well, that just plays havoc with trade.

Hygro

soundcloud.com/hygro/

Currency stability isn't an achievable concept to begin with.

Ajidica

High Quality Person

- Joined

- Nov 29, 2006

- Messages

- 22,482

This may be more of a historical question, but here it goes.

During the post-war years in Europe, European counties -especially Britain- placed a heavy emphasis on maintaining a strong currency which caused them no end of problems as they tried to run an expansionary fiscal policy.

Considering European economies at that time were largely export based, what advantages did they have in maintaining a strong currency given that lower currencies tend to make exporting easier?

(Or am I completely mucking up how currency works? I've always struggled wrapping my head around it.)

During the post-war years in Europe, European counties -especially Britain- placed a heavy emphasis on maintaining a strong currency which caused them no end of problems as they tried to run an expansionary fiscal policy.

Considering European economies at that time were largely export based, what advantages did they have in maintaining a strong currency given that lower currencies tend to make exporting easier?

(Or am I completely mucking up how currency works? I've always struggled wrapping my head around it.)

Hygro

soundcloud.com/hygro/

This may be more of a historical question, but here it goes.

During the post-war years in Europe, European counties -especially Britain- placed a heavy emphasis on maintaining a strong currency which caused them no end of problems as they tried to run an expansionary fiscal policy.

Considering European economies at that time were largely export based, what advantages did they have in maintaining a strong currency given that lower currencies tend to make exporting easier?

(Or am I completely mucking up how currency works? I've always struggled wrapping my head around it.)

You aren't mucking it up. The thing about strong and weak currencies is that the term refers only to the short run. In the long run, it doesn't matter if a currency trades 2:1 or 1:2 because domestic prices are going to vary, anyway. Recent changes in currency values will affect imports/exports because domestic prices change slower than international currency adjustments.

I know this doesn't answer your question, however.

I only know a bit about postwar export-oriented growth models, specifically that German export-driven growth was financed on the back of wage suppression. If they fought for strong currencies then perhaps it was to up the buying power of the capital-owning class so that they had access to technology (i.e. American stuff) to improve the types of products their cheap labor could produce? I'm speculating. I would have guessed the export-oriented countries worked to have cheap currencies.

Tahuti

Writing Deity

- Joined

- Nov 17, 2005

- Messages

- 9,492

I only know a bit about postwar export-oriented growth models, specifically that German export-driven growth was financed on the back of wage suppression. If they fought for strong currencies then perhaps it was to up the buying power of the capital-owning class so that they had access to technology (i.e. American stuff) to improve the types of products their cheap labor could produce? I'm speculating. I would have guessed the export-oriented countries worked to have cheap currencies.

Post-War German monetary policy is very tight, in part because doing otherwise evokes images of people using Marks as wallpapers. They exited Bretton-Woods when the US abandoned the Gold Standard to finance the Vietnam War. And this has worked to their advantage of creating an export economy, since it made it easier to bring in capital, as you rightly pointed out.

Overall, monetary appreciation in relation to other currencies isn't necessarily bad for export: It can be a signal that there is simple too little capital to go around. Making labour cheap won't fix that.

Austerity has been an unmitigated disaster, and this proves it

By Matt O'Brien April 24

http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs...n-an-unmitigated-disaster-and-this-proves-it/

By Matt O'Brien April 24

By Matt O'Brien April 24

(AFP/Getty Images/Louisa Gouliamakilouisa)

There's nothing more dangerous, when it comes to the economy, than getting cause and effect backwards.

That's how slowdowns turn into slumps, recessions turn into depressions, and recoveries turn into relapses. It's what the austerians did, though, when they insisted that cutting the deficit during a depression would actually help the economy by boosting confidence in the government's finances. It's an old fallacy that had been disproved in the 1930s, but came back from the intellectual dead in 2010 when people were looking for any excuse to do the economically inexcusable. So what had been hard-won knowledge became even harder still—if it was at all—as government threw one fiscal hurdle after another in front of the recovery out of fealty to some defunct economists. And that's why the IMF is trying to make sure we don't forget again that, yes, Keynes was right.

It's a pretty simple mistake. When the economy collapses, tax revenues do too, and the deficit goes up—and that's the way the causation runs. But the austerians look at this in reverse. They think the deficit, if not prompting the recession itself, is at least preventing a recovery by either making it too expensive for businesses to invest or scaring them out of doing it in the first place. In the depths of the Great Depression, for example, John Kenneth Galbraith tells us that the head of the New York Stock Exchange thought that "the government, not Wall Street, was responsible for the current bad times" and that the government "could make its greatest contribution to the recovery by balancing its budget and thus restoring confidence." Specifically, he wanted to cut "the pensions and benefits of veterans who had no service-related disability and also all government salaries." It was the same story almost 80 years later when then-European Central Bank chief Jean-Claude Trichet claimed that "the idea that austerity measures could trigger stagnation is incorrect" since "confidence-inspiring policies will foster and not hamper economic recovery, because confidence is the key factor today."

But why would businesses that don't have enough customers feel any more confident just because the government cut its spending? Good question. The austerians say it's that there's no such thing as not having enough customers, at least not for the economy as a whole. (If that doesn't make sense to you, don't worry, it doesn't). So if businesses aren't investing, the story goes, the best thing the government could do is to increase the pool of money that's available for investment by cutting its deficit. In other words, for the government to borrow less so the private sector can borrow for less. Not only that, but austerians say every dollar the government borrows is one it will have to pay back with higher taxes—meaning that, if businesses were clairvoyant, deficits would keep them from investing as much today so they could pay back the IRS tomorrow. Add it all up, and austerity should be expansionary, right?

Well, no. Less government borrowing can't lower private sector borrowing costs when interest rates are already zero, like they are now. And if you think you know what today's deficits mean for tomorrow's taxes, well, you probably think again. The private sector, in other words, won't spend any more to offset the government spending less—in fact, it will spend less. And that's not just a theory. That's what has happened. The IMF found that countries that have done austerity have actually had less investment afterwards. And even the ECB, which has forced countries to slash their deficits, now admits that these cuts "affect confidence negatively." This makes sense if you think that tax hikes and spending cuts hurt the economy, and people don't want to invest when the economy looks bad. It doesn't make sense, though, if you think that tax hikes and spending cuts make people feel so much better about the long-term fiscal outlook that they'll invest whether or not they have customers.

But the austerians don't make a lot of sense, do they? Empirical reality has shown over and over again that austerity makes a bad economy even worse, makes weak investment even weaker, and, in the process, shrinks the economy so much that total saving goes down even as these cuts try to force it up. So, as Keynes put it, "the boom, not the slump, is the time for austerity," because anything else is self-defeating. Unless the central bank can offset lower spending with lower interest rates, contractionary policy will be, well, contractionary. Although any of the millions of people who lost their jobs due to policymakers resurrecting an 80-year old delusion could have told you that.

But at least you don't have to wait until the long run for austerity to be dead as an intellectual concept.

http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs...n-an-unmitigated-disaster-and-this-proves-it/

Similar threads

- Replies

- 39

- Views

- 2K

- Replies

- 14

- Views

- 672

- Replies

- 4

- Views

- 314