More money is indeed always nice, I suppose. Most kings just debase their coinage or confiscate assets.What about the short term effects? Would it give a war advantage?

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

NES Economics Thread

- Thread starter Masada

- Start date

"Antiquity" isn't all that specific.

A ginormous rise in interest rates next time around. And since everybody borrows money...if you're even lent to at all after that particular debacle, of course. Look at the disparity between the interest rates at which Great Britain and France could borrow money in the late 18th century. (That's also assuming that, in the Middle Ages, there exists sufficient banking apparatus to allow you to borrow on that scale. Fuggers ain't around yet, for example.)

Okay, until 450 A.D or so, or whenever you think the western Roman Empire fell. (which seems to be at several different dates according to several different historians)

The spike in interest rates is guaranteed, it would also be likely that the only people you can borrow significant sums of money from would be your nobles in most cases (England had wool merchants, the Italians shipping magnates etc), short answer again you would likely hang or be removed or be marginalized if your nobility is powerful enough…

There are other effects, one could raise large sums of money but spending it would be another thing entirely, for instance the first 100 soon-to-be soldiers would be cheaper call it $2 each whether it be because they are fleeing oppressive masters or for other reasons, as you scrape the barrel more the cost would rise to say $3 per hundred, since it would cost progressively more to get the more secure individuals.

Now you could conscript them, but that wouldn’t work very well either, the additional capital wouldn’t grant you much of an advantage. And any nobles coming to fight with your are already fighting, you might be able to induce a few more to come along, but I think the feudal obligations they owe to there liege would outstrip any financial remuneration offered (you could keep them in the field longer perhaps though).

In the long term it would severely damage your economy, if the interest rate from 5 to 10% then the cost of doing anything large has just doubled…

Debasing coinage tends to also severely damage your economy, the moment people get wind of it, they stop using coinage and substitute back to other things, you also end up with rampant unpredictable inflation if people cant calculate how much you’ve been ripping them of, if they can then the prices of goods in the economy will over a relatively short period (say 3 years) rise adjusted for the crimping of the coinage back to its real price.

Now onto some basic Malthusian thought which really characterizes the economy of the world till the beginning of the industrial revolution (variously put as between 1730-1830 in Great Britain)

Imagine for a moment that there is a river valley which is fertile in the basin and as one moves away from the river; which winds its way through the middle of the valley the fertility of the land drops.

Now imagine for a moment that we have 10 people, an equal mix of females and males, all of childbearing age, all with a partner of the other sex. Now each of these couples farms in the most fertile area of the valley, directly next to the river, they need only work an acre to sustain themselves comfortably. This comfort manifests itself in a better diet, and higher standard of living, which in turn increases fertility, so each of these couples has 4 children which survive to adulthood and marriage. The original generation dies out.

So now we have 40 people (a quadrupling of the population the pre-industrial age was not impossible unlikely but not impossible, a more realistic figure would be a doubling but I wanted to show the likely effects rather quickly). 5 couples gain the most fertile land, that of their parents, right next to the river, an need only manage an acre per person. 5 more of these couples begin to farm the land directly next to the original plots, the fertility has dropped only marginally and they must now farm 1 acre and a fifth (no real great additional burden). The other 10 couples are forced to farm even more marginal land, land which due to some event in the past now has a large amount of rocks on it; they must instead farm 3 acres to maintain the same living standard as there peers.

In the next generation, there is again a quadrupling of the population, the 40 becomes 160 with the second generation dying out. So the first 20 couples get the same land as there parents with no problems, they maintain there living standards at the level of their parents. The next 60 couples however are faced with a choice, they must move further out into the most marginal territory which requires a vast area some 6 acres for the first 30 to farm to maintain there living standards, with the next 30 requiring fully 30 acres to survive by virtue of some less intensive method of farming tied to unpredictable rainfall. This is the limit of arable earth in the valley; there is no more farmable area.

When the population is small the best farming land is in use, when the population grows the amount of land in use grows, but the returns for each additional portion of land in use declines as the second best land is bought into use followed by the third etc.

In the next generation, even if population growth slows down to a mere doubling the living standards in aggregate must fall! Since in we defined the earlier plots as being comfortable and not subsistence, in order for the extra population to survive their parents must split there plots in some means or these extra’s must find some means of survival by for instance working for the established farmers on the best plots…

So in order to support these extra’s the total sum of food production must increase despite an ever increasing marginal return to food production. So those with the top farmland, those with the second tier, and those with the third tier must amp up production to feed everyone or risk chaos. For a while they can, another few generations might roll by, in aggregate everyone is poorer since the land owning farmers are only just holding out their wealth, while the rest are getting progressively poorer as the cost of food rises. Eventually it will become impossible to sustain the population, something has to give, it could be in the form of famine, war or disease.

In this case all three are likely, famine when the final tipping point is reached where food production is insufficient to keep up with growth, war when the underclass rebel against what must seem to be gouging landlords (the decreasing returns in food to each unit of labor would increase prices) or disease caused by poor diet or somesuch. This is really a rather simple overview of a potential situation.

It can be put even more simply, food production increases arithmetically, while population increases exponentially, the natural propensity of population is therefore to outstrip its food sources. War, famine and disease are thus “positive” in a Malthusian world (I’ll write in more depth sometime soon, I’m still not satisfied with my example… it could be tighter, but I think it’s understandable to you average non economist).

@Matt00088 i'll try and get onto that, but it would be quite a large project, and you'll need to give me time to find sources.

There are other effects, one could raise large sums of money but spending it would be another thing entirely, for instance the first 100 soon-to-be soldiers would be cheaper call it $2 each whether it be because they are fleeing oppressive masters or for other reasons, as you scrape the barrel more the cost would rise to say $3 per hundred, since it would cost progressively more to get the more secure individuals.

Now you could conscript them, but that wouldn’t work very well either, the additional capital wouldn’t grant you much of an advantage. And any nobles coming to fight with your are already fighting, you might be able to induce a few more to come along, but I think the feudal obligations they owe to there liege would outstrip any financial remuneration offered (you could keep them in the field longer perhaps though).

In the long term it would severely damage your economy, if the interest rate from 5 to 10% then the cost of doing anything large has just doubled…

Debasing coinage tends to also severely damage your economy, the moment people get wind of it, they stop using coinage and substitute back to other things, you also end up with rampant unpredictable inflation if people cant calculate how much you’ve been ripping them of, if they can then the prices of goods in the economy will over a relatively short period (say 3 years) rise adjusted for the crimping of the coinage back to its real price.

Now onto some basic Malthusian thought which really characterizes the economy of the world till the beginning of the industrial revolution (variously put as between 1730-1830 in Great Britain)

Imagine for a moment that there is a river valley which is fertile in the basin and as one moves away from the river; which winds its way through the middle of the valley the fertility of the land drops.

Now imagine for a moment that we have 10 people, an equal mix of females and males, all of childbearing age, all with a partner of the other sex. Now each of these couples farms in the most fertile area of the valley, directly next to the river, they need only work an acre to sustain themselves comfortably. This comfort manifests itself in a better diet, and higher standard of living, which in turn increases fertility, so each of these couples has 4 children which survive to adulthood and marriage. The original generation dies out.

So now we have 40 people (a quadrupling of the population the pre-industrial age was not impossible unlikely but not impossible, a more realistic figure would be a doubling but I wanted to show the likely effects rather quickly). 5 couples gain the most fertile land, that of their parents, right next to the river, an need only manage an acre per person. 5 more of these couples begin to farm the land directly next to the original plots, the fertility has dropped only marginally and they must now farm 1 acre and a fifth (no real great additional burden). The other 10 couples are forced to farm even more marginal land, land which due to some event in the past now has a large amount of rocks on it; they must instead farm 3 acres to maintain the same living standard as there peers.

In the next generation, there is again a quadrupling of the population, the 40 becomes 160 with the second generation dying out. So the first 20 couples get the same land as there parents with no problems, they maintain there living standards at the level of their parents. The next 60 couples however are faced with a choice, they must move further out into the most marginal territory which requires a vast area some 6 acres for the first 30 to farm to maintain there living standards, with the next 30 requiring fully 30 acres to survive by virtue of some less intensive method of farming tied to unpredictable rainfall. This is the limit of arable earth in the valley; there is no more farmable area.

When the population is small the best farming land is in use, when the population grows the amount of land in use grows, but the returns for each additional portion of land in use declines as the second best land is bought into use followed by the third etc.

In the next generation, even if population growth slows down to a mere doubling the living standards in aggregate must fall! Since in we defined the earlier plots as being comfortable and not subsistence, in order for the extra population to survive their parents must split there plots in some means or these extra’s must find some means of survival by for instance working for the established farmers on the best plots…

So in order to support these extra’s the total sum of food production must increase despite an ever increasing marginal return to food production. So those with the top farmland, those with the second tier, and those with the third tier must amp up production to feed everyone or risk chaos. For a while they can, another few generations might roll by, in aggregate everyone is poorer since the land owning farmers are only just holding out their wealth, while the rest are getting progressively poorer as the cost of food rises. Eventually it will become impossible to sustain the population, something has to give, it could be in the form of famine, war or disease.

In this case all three are likely, famine when the final tipping point is reached where food production is insufficient to keep up with growth, war when the underclass rebel against what must seem to be gouging landlords (the decreasing returns in food to each unit of labor would increase prices) or disease caused by poor diet or somesuch. This is really a rather simple overview of a potential situation.

It can be put even more simply, food production increases arithmetically, while population increases exponentially, the natural propensity of population is therefore to outstrip its food sources. War, famine and disease are thus “positive” in a Malthusian world (I’ll write in more depth sometime soon, I’m still not satisfied with my example… it could be tighter, but I think it’s understandable to you average non economist).

@Matt00088 i'll try and get onto that, but it would be quite a large project, and you'll need to give me time to find sources.

Neverwonagame3

Self-Styled Intellectual

- Joined

- Sep 5, 2006

- Messages

- 3,549

What about hiring mercenaries? Could that be done by the suggested means?

Yes, especially cause mercs are widely used during that time period. Problem is that your money solution is a short-term one and as soon as you run out of your stolen cash the mercs get pissed because you're not paying them. Then they switch sides at the worst possible moment as the Swiss and others were wont to do.What about hiring mercenaries? Could that be done by the suggested means?

Neverwonagame3

Self-Styled Intellectual

- Joined

- Sep 5, 2006

- Messages

- 3,549

Alternately, though, you could hire the same amount of mercenaries for longer- thus allowing you to keep a long term mercenary force in the field.

Huh? Mercs are pretty wily guys; the condottieri, for example, are easily capable of fleecing you. You can either get a smaller force of mercenaries for a longer period of time or a large force for short time or something in the middle, but don't expect men whose livelihoods depend on the money they get from you to be inexperienced at negotiating a contract such that you can trick them into working for less.Alternately, though, you could hire the same amount of mercenaries for longer- thus allowing you to keep a long term mercenary force in the field.

The moment they figure out you have more funds, is the moment they increase the price... go luck trying to enforce your contract.

The short term effects might be beneficial, but the long term effects will cripple your war effort if the war keeps going. Assuming you keep your head or throne, there’s a very compelling reasons why deliberately borrowing to default is not done, it’s not done .

.

The short term effects might be beneficial, but the long term effects will cripple your war effort if the war keeps going. Assuming you keep your head or throne, there’s a very compelling reasons why deliberately borrowing to default is not done, it’s not done

.

.Neverwonagame3

Self-Styled Intellectual

- Joined

- Sep 5, 2006

- Messages

- 3,549

Huh? Mercs are pretty wily guys; the condottieri, for example, are easily capable of fleecing you. You can either get a smaller force of mercenaries for a longer period of time or a large force for short time or something in the middle, but don't expect men whose livelihoods depend on the money they get from you to be inexperienced at negotiating a contract such that you can trick them into working for less.

I meant an average-sized force for a longer period of time thanks to stolen money.

What Masada said. Unless you can keep your loan secret somehow (you can't) the mercenaries will demand more money and you're back to square one.I meant an average-sized force for a longer period of time thanks to stolen money.

@Bannana Lee,

It will be speculative, but another couple of things I need to know, is there a limit to the amount of goods being transported, and is there the cost of building said drive prohibitive...?

EDIT: For some fun please do read http://www.princeton.edu/~pkrugman/interstellar.pdf

Amount of goods is limited by the tonnage of the ships carrying them.

The drive shouldn't be too prohibitive, the closest analogy I could think of would probably be supertankers. No one can just build a drive as they like, but if people want to pool together it shouldn't be too hard.

Again, all this is just arbitrary constraints that I pulled out my arse so it will be purely speculative

In a rather large broad brush view of history, we end up with the following key things for the pre-industrial world:

Malthusian constraints apply;

Agriculture swallowed up the majority of the population and generated the majority of the states revenue (in most cases);

Economic growth for a significant period must have been near to 0 since the birth of Christ, if it had been a tepid 0.5% every year from 0 to 2000 (assuming that the year 0 had a per capita average of $400 Geary-Khamis dollars) the end result would have been a per capita GDP of some $8.6 Geary-Khamis dollars. So it was near enough to 0 to be unnoticeable to most people during the course of their lives. Even the most optimistic projections of growth from 0 to 1000 notes a mere doubling or a tripling of per capita GDP (and even then that’s generous) so a 1000 years granting a mere doubling or tripling of wealth per person on average. In comparison in the 172 years after 1820 per capita GDP in the UK grew tenfold while in the US it grew twentyfold;

Population over the first two million years of human history did not exceed 0.0001% per year, around 10,000 years ago with the advent of agriculture it rose to a clipping 0.036% per year, come the first century AD it was now barrelling along at a clipping 0.056%, passing to 0.5% around 1750, and finally 1% at the start of the 19 century.

Growth was driven either by, institutions (generally property rights, scientific rationalism, capital markets, which form the foundations for innovation and incentives etc), however blithely assuming that the economy of a pre-industrial nation must grow is rather irresponsible.

The first point is precisely why economics is called the Dismal Science. From Malthus himself, Second Edition of An Essay on the Principle of Population

"A man who is born into a world already possessed, if he cannot get subsistence from his parents on whom he has a just demand, and if the society do not want his labour, has no claim of right to the smallest portion of food, and, in fact, has no business to be where he is. At nature's mighty feast there is no vacant cover for him. She tells him to be gone, and will quickly execute her own orders, if he does not work upon the compassion of some of her guests. If these guests get up and make room for him, other intruders immediately appear demanding the same favour. The report of a provision for all that come, fills the hall with numerous claimants. The order and harmony of the feast is disturbed, the plenty that before reigned is changed into scarcity; and the happiness of the guests is destroyed by the spectacle of misery and dependence in every part of the hall, and by the clamorous importunity of those, who are justly enraged at not finding the provision which they had been taught to expect. The guests learn too late their error, in counter-acting those strict orders to all intruders, issued by the great mistress of the feast, who, wishing that all guests should have plenty, and knowing she could not provide for unlimited numbers, humanely refused to admit fresh comers when her table was already full."

To sum it up; that is the hell on earth of Malthus we have the following snippets; (borrowed from A Farewell to Alms)

Before 1800 income per person – the food, clothing, heat, light and housing available per head – varied across societies and epochs. But there was no upwards trend. A simple but power mechanism… the Malthusian trap, ensured that short term gains in income through technological advances were inevitably lost through population growth.

Thus the average person in the world of 1800 was no better off than the average person 100,000BC. Indeed in 1800 the bulk of the world’s population was poorer than their remote ancestors. The lucky denizens of wealthy societies such as eighteenth-century England or the Netherlands managed a lifestyle equivalent to the Stone Age… but the vast swath of humanity in East and South East Asia… eked out a living under conditions probably significantly poorer than those of cavemen.

The quality of life also failed to improve on any other observable dimension. Life expectancy was no higher in 1800 than for hunter gathers: thirty to thirty-five years. Stature a measure both of the quality of diet and of children’s diet and exposure… did not improve significantly.

While some might be screaming something to the effect of “No way!” Its instructive to remember that while there might be swings up in living conditions, and in wealth in a long view these were just “noise” in the figures and really represent no real upwards trend. As soon as living conditions and wealth rose, they pretty soon fell back.

The vast majority of human societies, from the original foragers of the African savannah through settled agrarian societies until about 1800, led an economic life shaped and governed by one simple fact: in the long run births had to equal deaths… The Malthusian model supplies the mechanism to explain this long run population stability. In the simplest form there are just three assumptions.

1. Each societies has a birth rate, determined by customs regulating fertility, but increasing with material living standards,

2. The death rate in each society declines as living standards increase,

3. Material living standards decline as population increase.

In a stationary population birth rates equal death rates.

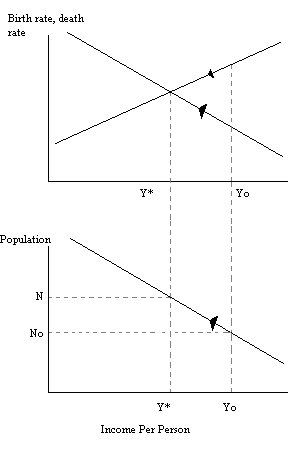

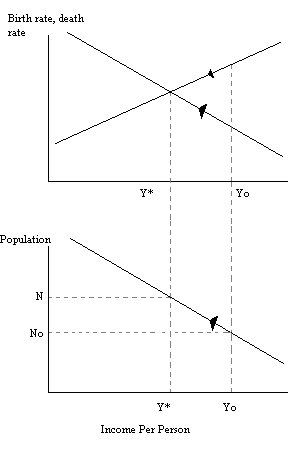

Basically the graph to explain the Malthusian model is rather simple.

The horizontal axis for both panels is material income, the amount of goods and services available to each person. In the top panel birth and death rates are plotted on the vertical axis. The material income at which birth equal death rates is called the subsistence income, indicated in the figure by y*. This is the income that just allows the population to reproduce itself. At material incomes above this the birth rate exceeds the death rate and population is growing. At material rates below this the death rate exceeds the birth rate and population declines. The subsistence income is determined without any reference to the production technology of the society. It depends only on the factors that determine the birth rate and those that determine the death rate. Once we know these we can determine the subsistence income and life expectancy at birth. In the bottom panel population is shown on the vertical axis, once we know population, that determines income and in turn the birth rate and death rates.

With just these assumptions it is easy to that the economy will always move in the long run to the level of real incomes at which birth rates equal death rates. Suppose population starts at an arbitrary initial population, No in the diagram. This will imply an initial income y0. Since yo exceeds the subsistence income, births exceed deaths and population grows. As it grows, income declines. As long as the income exceeds the subsistence level population growth will continue, and incomes will continue to fall. Only when the income has fallen to the subsistence level will population growth cease at the equilibrium level, N*, and the population stabilize.

Suppose that instead the initial population had been so large the income was below subsistence. Then deaths would exceed births and population would fall. This would push up incomes. The process would continue until income was again at subsistence level. Thus whenever population starts from in this society it always ends up at N*, with income at subsistence.

So why are there these assumptions?

The justification for the decline in material incomes with higher populations is as follows. Any production system employs a variety of inputs, the principal ones being land, labour, and capital. The law of diminishing returns holds that, if one of the inputs to production is fixed, then employing more of any of the other inputs to production will increase output but by progressively small increments. That is, the output per unit of the other input factors will decline as their use in production is expanded, as long as one input factor remains fixed.

In the preindustrial era land was the key production factor that was inherently fixed in supply. This limited supply implied that average output per worker would fall as the labour supply increased in any society, as long as the technology of that society remained unchanged. Consequently average material income per person fell with population growth.

Consider a peasant farmer with 50 acres of land. If he alone cultivates the land then he will maximize output by using low intensity cultivation methods: keeping cattle or sheep which are left to fend for themselves and periodically killed for meat and hides. With the labour of an additional person milk cows could also be kept, increasing total output. With yet more labour the property could be cultivated as arable land with grain crops. With even more people the land could be cultivated more intensely as garden land. Add 500 people and you will hit a wall, some of them will do nothing because there is no work they can do.

So what does this mean for Pre-Industrial NESing? It means in very simple terms that in all but the rarest cases; most of your income derives from agricultural sources. It also means that any increase in population all things held equal will decrease the wealth in aggregate of individuals. It also means that the more people you have the more fragile your economy is, assume for a moment that you have a drought with a low population people will flow to the areas where it is not so dry, with a large population that land will likely already be under cultivation and people will starve. It also means that your incomes are subject to the vagaries of changing seasons, to a large degree, if there is a crop failure the major source of your income has just collapsed. There is some degree of difference in the likely effects, some states have no sliding scale system, so even if there is a crop failure the people are still obliged to hand over the same amount of goods or payment, that is a quick way to head into feudalism, over a long period more and more people will inevitably fall into debt no matter how careful they are. With a sliding scale system you become subject to the seasons, if there is a crop failure your troops are likely to go hungry, if there is a bounty you gain a proportional increase.

Malthusian constraints apply;

Agriculture swallowed up the majority of the population and generated the majority of the states revenue (in most cases);

Economic growth for a significant period must have been near to 0 since the birth of Christ, if it had been a tepid 0.5% every year from 0 to 2000 (assuming that the year 0 had a per capita average of $400 Geary-Khamis dollars) the end result would have been a per capita GDP of some $8.6 Geary-Khamis dollars. So it was near enough to 0 to be unnoticeable to most people during the course of their lives. Even the most optimistic projections of growth from 0 to 1000 notes a mere doubling or a tripling of per capita GDP (and even then that’s generous) so a 1000 years granting a mere doubling or tripling of wealth per person on average. In comparison in the 172 years after 1820 per capita GDP in the UK grew tenfold while in the US it grew twentyfold;

Population over the first two million years of human history did not exceed 0.0001% per year, around 10,000 years ago with the advent of agriculture it rose to a clipping 0.036% per year, come the first century AD it was now barrelling along at a clipping 0.056%, passing to 0.5% around 1750, and finally 1% at the start of the 19 century.

Growth was driven either by, institutions (generally property rights, scientific rationalism, capital markets, which form the foundations for innovation and incentives etc), however blithely assuming that the economy of a pre-industrial nation must grow is rather irresponsible.

The first point is precisely why economics is called the Dismal Science. From Malthus himself, Second Edition of An Essay on the Principle of Population

"A man who is born into a world already possessed, if he cannot get subsistence from his parents on whom he has a just demand, and if the society do not want his labour, has no claim of right to the smallest portion of food, and, in fact, has no business to be where he is. At nature's mighty feast there is no vacant cover for him. She tells him to be gone, and will quickly execute her own orders, if he does not work upon the compassion of some of her guests. If these guests get up and make room for him, other intruders immediately appear demanding the same favour. The report of a provision for all that come, fills the hall with numerous claimants. The order and harmony of the feast is disturbed, the plenty that before reigned is changed into scarcity; and the happiness of the guests is destroyed by the spectacle of misery and dependence in every part of the hall, and by the clamorous importunity of those, who are justly enraged at not finding the provision which they had been taught to expect. The guests learn too late their error, in counter-acting those strict orders to all intruders, issued by the great mistress of the feast, who, wishing that all guests should have plenty, and knowing she could not provide for unlimited numbers, humanely refused to admit fresh comers when her table was already full."

To sum it up; that is the hell on earth of Malthus we have the following snippets; (borrowed from A Farewell to Alms)

Before 1800 income per person – the food, clothing, heat, light and housing available per head – varied across societies and epochs. But there was no upwards trend. A simple but power mechanism… the Malthusian trap, ensured that short term gains in income through technological advances were inevitably lost through population growth.

Thus the average person in the world of 1800 was no better off than the average person 100,000BC. Indeed in 1800 the bulk of the world’s population was poorer than their remote ancestors. The lucky denizens of wealthy societies such as eighteenth-century England or the Netherlands managed a lifestyle equivalent to the Stone Age… but the vast swath of humanity in East and South East Asia… eked out a living under conditions probably significantly poorer than those of cavemen.

The quality of life also failed to improve on any other observable dimension. Life expectancy was no higher in 1800 than for hunter gathers: thirty to thirty-five years. Stature a measure both of the quality of diet and of children’s diet and exposure… did not improve significantly.

While some might be screaming something to the effect of “No way!” Its instructive to remember that while there might be swings up in living conditions, and in wealth in a long view these were just “noise” in the figures and really represent no real upwards trend. As soon as living conditions and wealth rose, they pretty soon fell back.

The vast majority of human societies, from the original foragers of the African savannah through settled agrarian societies until about 1800, led an economic life shaped and governed by one simple fact: in the long run births had to equal deaths… The Malthusian model supplies the mechanism to explain this long run population stability. In the simplest form there are just three assumptions.

1. Each societies has a birth rate, determined by customs regulating fertility, but increasing with material living standards,

2. The death rate in each society declines as living standards increase,

3. Material living standards decline as population increase.

In a stationary population birth rates equal death rates.

Basically the graph to explain the Malthusian model is rather simple.

The horizontal axis for both panels is material income, the amount of goods and services available to each person. In the top panel birth and death rates are plotted on the vertical axis. The material income at which birth equal death rates is called the subsistence income, indicated in the figure by y*. This is the income that just allows the population to reproduce itself. At material incomes above this the birth rate exceeds the death rate and population is growing. At material rates below this the death rate exceeds the birth rate and population declines. The subsistence income is determined without any reference to the production technology of the society. It depends only on the factors that determine the birth rate and those that determine the death rate. Once we know these we can determine the subsistence income and life expectancy at birth. In the bottom panel population is shown on the vertical axis, once we know population, that determines income and in turn the birth rate and death rates.

With just these assumptions it is easy to that the economy will always move in the long run to the level of real incomes at which birth rates equal death rates. Suppose population starts at an arbitrary initial population, No in the diagram. This will imply an initial income y0. Since yo exceeds the subsistence income, births exceed deaths and population grows. As it grows, income declines. As long as the income exceeds the subsistence level population growth will continue, and incomes will continue to fall. Only when the income has fallen to the subsistence level will population growth cease at the equilibrium level, N*, and the population stabilize.

Suppose that instead the initial population had been so large the income was below subsistence. Then deaths would exceed births and population would fall. This would push up incomes. The process would continue until income was again at subsistence level. Thus whenever population starts from in this society it always ends up at N*, with income at subsistence.

So why are there these assumptions?

The justification for the decline in material incomes with higher populations is as follows. Any production system employs a variety of inputs, the principal ones being land, labour, and capital. The law of diminishing returns holds that, if one of the inputs to production is fixed, then employing more of any of the other inputs to production will increase output but by progressively small increments. That is, the output per unit of the other input factors will decline as their use in production is expanded, as long as one input factor remains fixed.

In the preindustrial era land was the key production factor that was inherently fixed in supply. This limited supply implied that average output per worker would fall as the labour supply increased in any society, as long as the technology of that society remained unchanged. Consequently average material income per person fell with population growth.

Consider a peasant farmer with 50 acres of land. If he alone cultivates the land then he will maximize output by using low intensity cultivation methods: keeping cattle or sheep which are left to fend for themselves and periodically killed for meat and hides. With the labour of an additional person milk cows could also be kept, increasing total output. With yet more labour the property could be cultivated as arable land with grain crops. With even more people the land could be cultivated more intensely as garden land. Add 500 people and you will hit a wall, some of them will do nothing because there is no work they can do.

So what does this mean for Pre-Industrial NESing? It means in very simple terms that in all but the rarest cases; most of your income derives from agricultural sources. It also means that any increase in population all things held equal will decrease the wealth in aggregate of individuals. It also means that the more people you have the more fragile your economy is, assume for a moment that you have a drought with a low population people will flow to the areas where it is not so dry, with a large population that land will likely already be under cultivation and people will starve. It also means that your incomes are subject to the vagaries of changing seasons, to a large degree, if there is a crop failure the major source of your income has just collapsed. There is some degree of difference in the likely effects, some states have no sliding scale system, so even if there is a crop failure the people are still obliged to hand over the same amount of goods or payment, that is a quick way to head into feudalism, over a long period more and more people will inevitably fall into debt no matter how careful they are. With a sliding scale system you become subject to the seasons, if there is a crop failure your troops are likely to go hungry, if there is a bounty you gain a proportional increase.

das

Regeneration In Process

over a long period more and more people will inevitably fall into debt no matter how careful they are.

What if we place a religious prohibition on usury and combine it with Chinese-style economic support? I understand that the former is possible to evade in one way or another, while the latter is going to be subject to some serious corruption, but this still should rein in such things (and partly ****** economic development, but I'm not sure if maximum inequity stimulates it either; generally development happens somewhere between the extremes of equality and inequity, and bureaucratic and feudal control).

Anyway, a nice summary, but what about trade income? It can amount for a lot at times, mostly for the middle men, though it carries with it economic dependency.

Neverwonagame3

Self-Styled Intellectual

- Joined

- Sep 5, 2006

- Messages

- 3,549

Another economic scenario:

Power A attacks Power B. Power B is distracted elsewhere, and so attempts to hamper Power A's attack by (sucessfully) printing massive amounts of Power A currency and sending it into their economy. Result?

Power A attacks Power B. Power B is distracted elsewhere, and so attempts to hamper Power A's attack by (sucessfully) printing massive amounts of Power A currency and sending it into their economy. Result?

das

Regeneration In Process

A more specific hypothetical scenario that occurred to me, related to the Silk Route. It occurs to me that the northern "arm" of the Silk Route in the Middle Ages extended through the Black Sea steppe and modern Romania, where the locals were unable to take advantage of it properly. Suppose, however, that an urban civilisation was preserved to a greater extent in the coastal regions beyond Crimea and Kerch; possibly due to more extensive Roman conquests in the area early on and then thanks to the presence of an unusually awesome fictional Roman governor in a critical time. That governor could have fended off some barbarians and put others into his service, using them to break away and set up his own kingdom, deflecting various barbarians that would be more eager to attack easier and wealthier prey. The kingdom might not survive, but if he patronises the cities we might have at least something on the level of the early Medieval Adriatic city-states by the time when the main migrations more or less die down and the Silk Route reaches the area. The region of the eastern Danube was very prosperous even in OTL; here it might become one of the main economic centers, at least for two-three centuries, possibly being either contested between the Rus and the Byzantines or becoming an economic backbone for the First Bulgarian Empire.

Is something like that possible, and will it be able to have a major effect on the overall economic patterns in Europe? And, if we go with the Bulgarian variant, could such income be enough/be exploited in a way that will, given the right leadership, allow the First Bulgarian Empire to survive?

Is something like that possible, and will it be able to have a major effect on the overall economic patterns in Europe? And, if we go with the Bulgarian variant, could such income be enough/be exploited in a way that will, given the right leadership, allow the First Bulgarian Empire to survive?

There are two “camps” with regards to micro-lending to subsistence farmers.

The first camp inevitably are left leaning economists tend to hold that lending to subsistence farmers is the root of all evil, that they get in debt, are unable to repay it and end up owing money to exploitative capitalists or land-owners or something to that effect. It’s been a commonly held idea since Biblical days, Israel apparently forgave debts every 7 years (which is probably an invention by the concept stands) and there were similar legal recourses in most states.

The second camp which tends to be made up of right leaning economists tend to hold that lending to subsistence farmers is actually needed, since they tend to have sporadic incomes (harvest time) and tend to only be able to store their produced goods for a short period (owing to a total dependence on what they themselves have made), micro credit lending is therefore important in allowing farmers to weather the periods in between. Farers typically only ever borrow a small amount, and they tend to be for goods like tools and other necessities, tough luck if you have no access to financial markets and your hoe breaks just before harvest and you yourself have no money having weathered a rather bad year.

I tend to sit in the second camp, having talked to more than a few subsistence farmers about the issue, they understand that the interest rates might be significant, but if they are borrowing they are borrowing for a very important reason.

Just as a note, debt quite often means a debt to the state or its tax collectors or tax farmers, after a while of not being able to pay the set rate, you default on your debt, the state or it s representative take over your land and welcome to serfdom. It would not be some common to actually “borrow” from a financial institution, one is far more likely to borrow from the local landed wealth, or the nearest large farmer neighbour and standard prohibitions on lending tend to fall out of favour rather quickly, they can be circumvented rather easily (by not charging interest but by for instance giving a loan to an individual farmer, and instead of paying it back requiring that farmer and his family to supply you with the set product of an area of the farm or something of that nature in effect a perpetual annuity).

If we were to zoom out, banning lending in a general sense would cripple your economy, absolutely utterly devastate it, the effects might not be immediately noticeable in a pre-modern economy which is rather slow to react to changes in market conditions. Firms though that would normally survive some sort of business calamity by borrowing would not survive, so I would expect to see within a significant period (call it 20 years or more assuming no major disaster happens in the interim), to see a significant decline in the number or firms in the market, and probably negative growth.

Economic support would probably cause a fair few problems as well (if you mean a grain dole or some similar measure), in the short term it’ll cushion against instability, and raise the population. Assume the rate at which people qualify for assistance is $3 and the majority of the population are at $4 income, what happens when all those who qualify for assistance continue to generate children… the lot of the group as a whole falls and more people come in under the assistance rate which means that increasing sums of money are diverted to providing relief for the poor (who in reality might not be poor, the true value of the currency could have risen in the meantime, but it would be politically unfeasible to remove the assistance). This is also a common thing for the state to do to cover the increasing liabilities on the balance sheet, they begin setting artificially low prices and begin all out seizures of grain, they can do this by requiring that a set portion of the harvest be held over for the states use and then just paying under the market rate… the likely result of this or anything similar is to have people plant cash crops…

I do grant that trade can be a major boon to the states which are in the middle of it, but the dependence isn’t the only threat, Dutch disease is another probable result as is classic renter behaviour. Having all that money just floating on through, tends to stunt the internal competitiveness of your nation, you will certainly be wealthy but your internal economy will be anaemic. The other natural result is renter behaviour; it becomes far easier to just live of the easy money, it’s not uncommon to have the middle man never engage in the trade themselves far more content to just other do it… the silk road is a good example, your average middleman in that did not engage directly in the carrying of silk or for that matter all that much aside from a protection racket with a supply function. This is a-bit general, mind, there are always exceptions, any specific NES mod questions you have can be directed to me privately and I will keep them confidential.

EDIT: Reading your second question now

EDIT: @NWAG, they might be able to wreak economic havoc, but the difficulty is not being found out, you need to spend the money in the economy, the likely result is an upsurge in inflation and maybe other problems, of course a canny state will just change it's presses, wack of a zero and honour all currency trades to the new one. And probably return the favour.

The first camp inevitably are left leaning economists tend to hold that lending to subsistence farmers is the root of all evil, that they get in debt, are unable to repay it and end up owing money to exploitative capitalists or land-owners or something to that effect. It’s been a commonly held idea since Biblical days, Israel apparently forgave debts every 7 years (which is probably an invention by the concept stands) and there were similar legal recourses in most states.

The second camp which tends to be made up of right leaning economists tend to hold that lending to subsistence farmers is actually needed, since they tend to have sporadic incomes (harvest time) and tend to only be able to store their produced goods for a short period (owing to a total dependence on what they themselves have made), micro credit lending is therefore important in allowing farmers to weather the periods in between. Farers typically only ever borrow a small amount, and they tend to be for goods like tools and other necessities, tough luck if you have no access to financial markets and your hoe breaks just before harvest and you yourself have no money having weathered a rather bad year.

I tend to sit in the second camp, having talked to more than a few subsistence farmers about the issue, they understand that the interest rates might be significant, but if they are borrowing they are borrowing for a very important reason.

Just as a note, debt quite often means a debt to the state or its tax collectors or tax farmers, after a while of not being able to pay the set rate, you default on your debt, the state or it s representative take over your land and welcome to serfdom. It would not be some common to actually “borrow” from a financial institution, one is far more likely to borrow from the local landed wealth, or the nearest large farmer neighbour and standard prohibitions on lending tend to fall out of favour rather quickly, they can be circumvented rather easily (by not charging interest but by for instance giving a loan to an individual farmer, and instead of paying it back requiring that farmer and his family to supply you with the set product of an area of the farm or something of that nature in effect a perpetual annuity).

If we were to zoom out, banning lending in a general sense would cripple your economy, absolutely utterly devastate it, the effects might not be immediately noticeable in a pre-modern economy which is rather slow to react to changes in market conditions. Firms though that would normally survive some sort of business calamity by borrowing would not survive, so I would expect to see within a significant period (call it 20 years or more assuming no major disaster happens in the interim), to see a significant decline in the number or firms in the market, and probably negative growth.

Economic support would probably cause a fair few problems as well (if you mean a grain dole or some similar measure), in the short term it’ll cushion against instability, and raise the population. Assume the rate at which people qualify for assistance is $3 and the majority of the population are at $4 income, what happens when all those who qualify for assistance continue to generate children… the lot of the group as a whole falls and more people come in under the assistance rate which means that increasing sums of money are diverted to providing relief for the poor (who in reality might not be poor, the true value of the currency could have risen in the meantime, but it would be politically unfeasible to remove the assistance). This is also a common thing for the state to do to cover the increasing liabilities on the balance sheet, they begin setting artificially low prices and begin all out seizures of grain, they can do this by requiring that a set portion of the harvest be held over for the states use and then just paying under the market rate… the likely result of this or anything similar is to have people plant cash crops…

I do grant that trade can be a major boon to the states which are in the middle of it, but the dependence isn’t the only threat, Dutch disease is another probable result as is classic renter behaviour. Having all that money just floating on through, tends to stunt the internal competitiveness of your nation, you will certainly be wealthy but your internal economy will be anaemic. The other natural result is renter behaviour; it becomes far easier to just live of the easy money, it’s not uncommon to have the middle man never engage in the trade themselves far more content to just other do it… the silk road is a good example, your average middleman in that did not engage directly in the carrying of silk or for that matter all that much aside from a protection racket with a supply function. This is a-bit general, mind, there are always exceptions, any specific NES mod questions you have can be directed to me privately and I will keep them confidential.

EDIT: Reading your second question now

EDIT: @NWAG, they might be able to wreak economic havoc, but the difficulty is not being found out, you need to spend the money in the economy, the likely result is an upsurge in inflation and maybe other problems, of course a canny state will just change it's presses, wack of a zero and honour all currency trades to the new one. And probably return the favour.

das

Regeneration In Process

there were similar legal recourses in most states.

Seisachtheia would be one of them, right? I assume that it was done in places other than Athens as well. Still, what would be its impact?

Just as a note, debt quite often means a debt to the state or its tax collectors or tax farmers,

But it also quite often means a debt to entirely private persons, at which point state interests are usually against it. Then again, I guess that publicans in Ancient Rome were pretty much private as well.

If we were to zoom out, banning lending in a general sense would cripple your economy, absolutely utterly devastate it, the effects might not be immediately noticeable in a pre-modern economy which is rather slow to react to changes in market conditions. Firms though that would normally survive some sort of business calamity by borrowing would not survive, so I would expect to see within a significant period (call it 20 years or more assuming no major disaster happens in the interim), to see a significant decline in the number or firms in the market, and probably negative growth.

So in other words it would cripple the larger trading associations and generally ****** the further development of the urban segment of the economy. On the other hand, it should also hinder socio-economic stratification (at the expense of, well, death of many of the people you are trying to save from debt slavery), and might benefit some individual traders.

your average middleman in that did not engage directly in the carrying of silk or for that matter all that much aside from a protection racket with a supply function.

Hence the what-if; I suppose that developed trading cities were not above such things themselves, but if anything they would carry it out more intelligently, and might reap a far better profit than comparatively primitive tribal communities (whose own development was indeed majorly ******** by the whole thing).

The Bosporan Kingdom seemed to have worked okay...but. I know that the Huns and Alans on their way west in the late fourth century probably trashed the cities, though. And since the rich northern Black Sea coast was one of the primary motivators for the Hunnic original movement I can't see them not stopping to sack said cities. You could instead have it revolt similar to that independent Exarchate of Carthage plan you once proposed, during the Muslim invasions of the seventh century, and create an independent Cimmerian Bosporan-Roman/Byzantine kingdom out of that. The Eastern Romans did lead something of a Bosporan revival a century after the Huns rolled through, after all.Is something like that possible,

Another problem with the mechanics of what you originally proposed is that Roman Cimmerian Bosporus was never actually subjugated and remained a client state officially until the Hunnic invasion. The kings in Panticapaeum never really had much of a reason to throw off the Roman protectorate, because the Romans were easily less of a drain than the raiding steppe tribes that Roman troops helped fend off.

das

Regeneration In Process

I was taking more about Dacia, though (or modern Romania and its surroundings in general), in case you did not understand. The Bosporus is sort of different. As for Huns, well, that's a tough one.  Okay, the thing is to bribe them off and accept their nominal sovereignty until they go away or to defend from the fortified cities until they decide to go after something juicier, like Rome.

Okay, the thing is to bribe them off and accept their nominal sovereignty until they go away or to defend from the fortified cities until they decide to go after something juicier, like Rome.

Okay, the thing is to bribe them off and accept their nominal sovereignty until they go away or to defend from the fortified cities until they decide to go after something juicier, like Rome.

Okay, the thing is to bribe them off and accept their nominal sovereignty until they go away or to defend from the fortified cities until they decide to go after something juicier, like Rome.Similar threads

- Replies

- 3

- Views

- 516

- Replies

- 11

- Views

- 904

- Replies

- 44

- Views

- 4K