You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The thread for space cadets!

- Thread starter hobbsyoyo

- Start date

Winner

Diverse in Unity

I think there are lots of planets similar to Titan though it will be a while before we can spot them. I think one of the other factors that allows Titan to exist as it does with a methane cycle and dense atmosphere is it's distance from the Sun. If it were closer, I would think that it's atmosphere would have been stripped by the solar wind the way Mar's was - though I don't know if Titan has a magnetosphere. Also, I guess being in Saturn's magnetosphere would have helped with that as well.

Yeah, that's my line of thinking too. OTOH, Titan's atmosphere is mostly nitrogen (like Earth's, curiously). I'd say Titan's size is the key - if it was smaller, it would have lost its atmosphere no matter what. Also, if it was closer, it's size would be of no help either, as Ganymede and Callisto can attest. The only other moon with *some* noticeable atmosphere is Triton, but even that far from the sun it is difficult to hold it (and it tends to freeze

).

). I don't know if rocky planets can exist further out from their host stars than Mars without being a satellite. The only data we have at the moment suggests the answer is no, but that's basically exclusively based on our solar system as we can't currently detect small, rocky planets at AUish distances from their host stars.

Yeah. I wondered whether there could be super-terrestrial planets in the outer reaches of other solar system, basically as "failed gas giants". AFAIK gas giants first form like giant balls of rock and ice, which then start accreting gas until they turn into sub-Jovians (or ice dwarfs like Uranus and Neptune) or, if there is enough gas in the protoplanetary at their orbital distance, into fully fledged gas giants.

I wondered what would happen to these proto-gas giant cores if something interrupted the gas accretion process (giant impact, orbital shifts due to close encounters with other planets, etc.). I think they could essentially end up being Titans on steroids - many times the Earth mass, with very dense and heavy atmosphere (something akin to Venus), but very cold and boasting a methane hydrological cycle.

Alternatively, smaller terrestrial planets could have been ejected from the inner solar system and end up in a region where a methane cycle can sustain itself. The early Earth had, as far as I know, a lot of methane in its primordial atmosphere.

Then there is of course the "boring" option of having a gas giant with an Earth or Mars sized moons, which I think is entirely imaginable. Put them in the right distance, and you can have a super-Titan.

Glad to see you back here Winner.

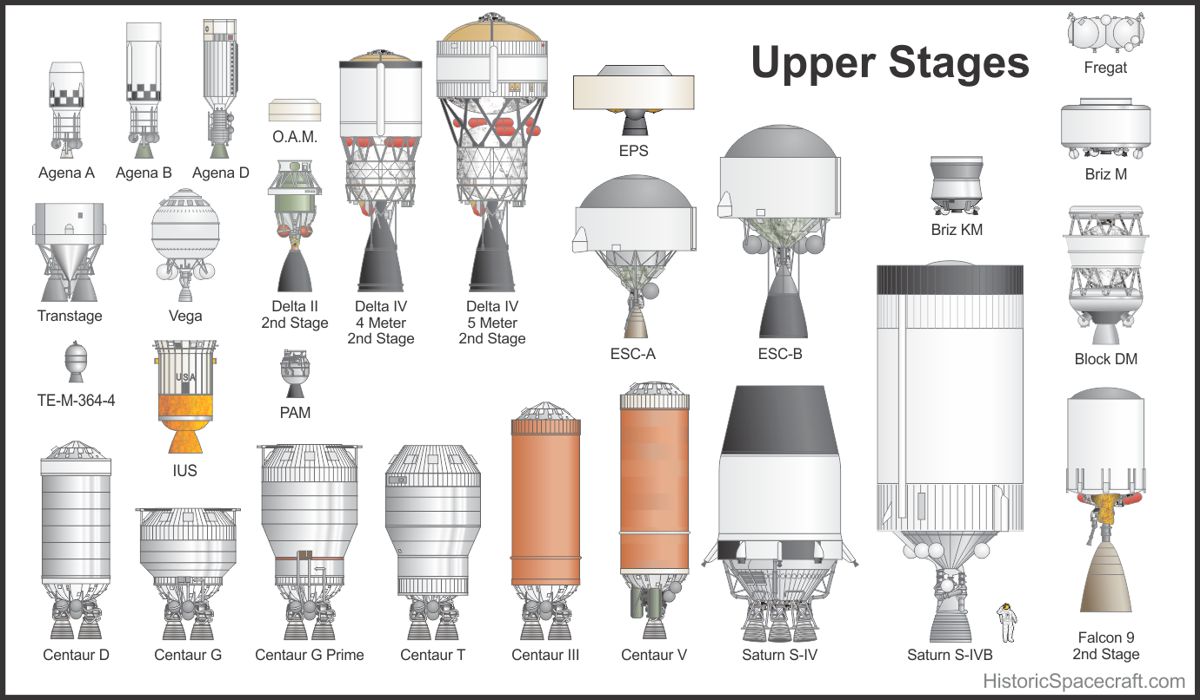

Don't know for how long (exaaaams), but let's celebrate with some graphic rocket porn:

http://historicspacecraft.com/index.html

Spoiler :

BTW isnt Titan supposed to be covered with methane seas? I only see yellow rocks there.

That's what had originally been assumed. Then came the disillusionment, and then more excitement when large bodies of liquid hydrocarbon were found at the poles.

It *seems* that Titan is actually pretty hot and arid for the methane hydrological cycle to be perpetual, and it has a weird climate which includes "wet" seasons with torrential rains (which form all these river basins we've seen in Hyugens' photos) followed by "dry" seasons when nothing much is happening.

(But it may be completely different, this is just what I remember from a few articles I read about this. I think nobody really knows what is really happening on that moon as of yet).

How could would it be to have a rover down there?

Would something like that even be theoretically possible?

Sure. But right now I think people are more interested in sending either a balloon which would float in Titan's atmosphere and cover a larger area of the surface, or a floating probe to land in one of the polar methane/ethane lakes.

The problem is that Saturn is pretty far, which means travelling there requires either a big rocket or lots of time (for multiple gravity assists alá Cassini's trajectory), and you can't rely on solar energy for powering your probes that far from the Sun. Communication also isn't that easy.

So, for the time being, let's hope Cassini lasts for many more years, because it will be some time before we return to the Saturn system. (Which is a shame, but what one do...)

hobbsyoyo

Deity

- Joined

- Jul 13, 2012

- Messages

- 26,575

Do we have evidence Ganymede and Callisto had atmosphere's that were stripped? Is it possible they didn't have one to begin with or lost it for other reasons? (I have no clue)Yeah, that's my line of thinking too. OTOH, Titan's atmosphere is mostly nitrogen (like Earth's, curiously). I'd say Titan's size is the key - if it was smaller, it would have lost its atmosphere no matter what. Also, if it was closer, it's size would be of no help either, as Ganymede and Callisto can attest. The only other moon with *some* noticeable atmosphere is Triton, but even that far from the sun it is difficult to hold it (and it tends to freeze).

I agree and from what we're seeing with exo-planets, it may be possible that we don't really have a clue how solar systems *tend* to form as so many of the ones we find are breaking our formation models. Maybe you can have small rocky planets far out that weren't failed giants through mechanisms we don't understand. Or maybe we can't. This is such a rapidly changing field of study it's pretty fascinating to watch and literally see long-held assumptions fall apart day by day.Yeah. I wondered whether there could be super-terrestrial planets in the outer reaches of other solar system, basically as "failed gas giants". AFAIK gas giants first form like giant balls of rock and ice, which then start accreting gas until they turn into sub-Jovians (or ice dwarfs like Uranus and Neptune) or, if there is enough gas in the protoplanetary at their orbital distance, into fully fledged gas giants.

Do they know if the methane had a biogenesis or if it was just a natural chemical reaction? Hmm now I wonder how Titan got it's methane...I guess it's just a common compound in the universe (it is a really simple molecule) that just happens to break down in UV light so it has to be replenished closed to the sun.Alternatively, smaller terrestrial planets could have been ejected from the inner solar system and end up in a region where a methane cycle can sustain itself. The early Earth had, as far as I know, a lot of methane in its primordial atmosphere.

After Endor, Earth-sized moons are pretty boring!Then there is of course the "boring" option of having a gas giant with an Earth or Mars sized moons, which I think is entirely imaginable. Put them in the right distance, and you can have a super-Titan.

Good luck, thanks for the awesome pics!Don't know for how long (exaaaams), but let's celebrate with some graphic rocket porn:

what are the testicles dangling just above the nozzles in the rocketpr0n?

I'm going to guess liquid oxygen. Survey says....?

I'm going to guess liquid oxygen. Survey says....?

Winner

Diverse in Unity

Do we have evidence Ganymede and Callisto had atmosphere's that were stripped? Is it possible they didn't have one to begin with or lost it for other reasons? (I have no clue)

I imagine they might have (no clue either). I mean, they have ice surfaces, so if they were hotter earlier in their evolution, they must have had some evaporation and thus *some* atmosphere. How long and how thick , I have no idea. I just guess that since Ganymede and Titan are very similar in size and quite possibly in internal structure as well (there is some evidence that both have active interiors), Ganymede would end up looking like Titan if it was a bit farther from the Sun.

Of course I am probably totally wrong for some reasons I failed to account for (like, say, the interaction between Jupiter's moons and its gigantic radiation belts, or the heat Jupiter might have been radiating early on, or the cometary impacts Jupiter seems to be attracting, etc. etc. etc. - there are so many possibilities).

Anyway, Io has something of a trace atmosphere from its active volcanism, but can't hold to it due to its small size.

This is such a rapidly changing field of study it's pretty fascinating to watch and literally see long-held assumptions fall apart day by day.

Wholeheartedly seconded. I find it fascinating how our cherished planetary formation models based on one example we're reasonably familiar with (the solar system) were swept away in just one decade of exoplanet hunting and better computer modelling

We basically went from the orderly "planets formed where the are today" to "it was total chaos and we're damn lucky we're even here". I read just a few days ago an article on Wiki about this, and there I read that Neptune originally formed *closer* to the Sun than Uranus, but when Jupiter and Saturn got locked into 1:2 orbital resonance, Neptune was thrown out into the (then much bigger, denser, and closer) Kuiper belt where its orbit gradually circularized due to its interaction with the ice objects (who were scattered as result of that). It seems that these debris discs are actually quite important in determining where planets end up.

Oh, BTW, I also found this 4-body "solar system" simulator. It's quite fun to see how your planets get scattered, shift orbits, and whatnot. And now one has to imagine that not with 4 centres of gravity, but 10, 20, 50, 100, or more. It's mind boggling (and no wonder we need supercomputers for simulating that).

Do they know if the methane had a biogenesis or if it was just a natural chemical reaction? Hmm now I wonder how Titan got it's methane...I guess it's just a common compound in the universe (it is a really simple molecule) that just happens to break down in UV light so it has to be replenished closed to the sun.

No idea. I read something about methane being replenished by cryvolcanism - essentially that there is plenty of methane inside of Titan, which is slowly leaking into the atmosphere, thus replenish the methane lost to UV dissociation. No idea how correct that theory is.

After Endor, Earth-sized moons are pretty boring!

Ah, that's the moon from SW? I am only broadly familiar with that universe

I'd love to know though whether the size of moons really depend on the size of the gas giant, or if there can be exceptions (like when you have Saturn-size planet with an Earth-size Moon - which is the case in Avatar, I believe.

I'd love to know though whether the size of moons really depend on the size of the gas giant, or if there can be exceptions (like when you have Saturn-size planet with an Earth-size Moon - which is the case in Avatar, I believe.---

Oh BTW, I gave the Kerbal Space Program a try. Worst - idea - ever!!! Instead of studying, I've spend hours on end playing around the little solar system like a little boy playing with lego rockets. Oh well...

what are the testicles dangling just above the nozzles in the rocketpr0n?

I'm going to guess liquid oxygen. Survey says....?

Oxidizer/fuel tanks are bigger, they're inside the stage. I think the little balls are either tanks with helium or some other gas used for pressurizing the main tanks, or propellant tanks for smaller rocket motor used to steer the stage. Or the stuff used to ignite/reignite the main engine. You'll have to ask an engineer about that

I like Titan, and I think it will be easier to send probes there to explore what we want to explore, but I think (easily) that the ice-moons should get priority. Firstly, Europa, asap. Then, the other icy moons based on the likelihood of water seas. But we need to get a probe on Europa. And under its ice. Swarm that place with satellites, too.

Ben Bova thinks so.How could would it be to have a rover down there?

Would something like that even be theoretically possible?

Titan.

Titan.Winner

Diverse in Unity

I like Titan, and I think it will be easier to send probes there to explore what we want to explore, but I think (easily) that the ice-moons should get priority. Firstly, Europa, asap. Then, the other icy moons based on the likelihood of water seas. But we need to get a probe on Europa. And under its ice. Swarm that place with satellites, too.

Well, we talked about that. If the goal of planetary exploration is to A) find life; B) find life; C) find life; D) find life; (....) Z) ...and maybe do some other interesting stuff as well, then by all means.

I for one would like my programme more diversified. In this case, my rationale is that even if there are microbes in Europa's oceans (IF they exist), they'll be pretty hard to get to, and even harder to get back to Earth for proper analysis (I doubt we'll be able to properly study them using only remotely operated robotic instruments, but maybe I'll be surprised).

The thing is, missions to outer solsys are expensive, they take a lot of time, so the pay-off better be worth it. From what I read, Titan has something for everybody, including the possibility of harbouring some form of life. I for one would find the discovery of some freaky liquid-methane based organisms pretty shocking.

(well, this response doesn't really have a point, so treat it as a rant)

Ben Bova thinks so.Titan.

Also, Titan is the name of a novel by Stephen Baxter. A very gloomy and bitter one, I might add (I still don't know whether he meant it seriously, or as a cautionary tale/commentary on the growing stupidness of human population). For someone who's never been in space, Baxter can really drive home the message that spending years in a pressurized can living on closed loop life support ain't no fun.

I wasn't talking about Baxter, Varley, or anyone else who's written about Titan - only Ben Bova. One of the major story threads in this novel is about the team of scientists involved in sending a rover-type probe to the surface of Titan, and the methods they use to solve the problems that crop up (ie. how do you fix the thing when it goes incommunicado?).

http://www.planetaryresources.com/2013/05/planetary-resources-opening-the-space-frontier-to-all/

The whole citizen science thing could really take off. I've used my computer for folding at home. I spent some time IDing galaxies. Finally, and I've been a fan of asteroid mining for a number of years, we might be able to get some use out of all the fanbois out there. It's a way of helping without giving money, but it's really actually helping

On May 29 at 10:00 a.m. PDT in Seattle, and also streaming live, please join Planetary Resources’ Peter Diamandis, Eric Anderson and Chris Lewicki, as they, along with vlogger Hank Green, announce an unprecedented project that will change the way humanity explores the cosmos.

Program Highlights:

Gives students, teachers and the public access to the most innovative space observation technology ever built – This technology would have cost US$100M+ to build and launch less than a decade ago; and today, it will be controlled by students around the world to explore the cosmos.

Offers the opportunity for the public to directly participate in cutting-edge citizen science and discovery – Delivers a resource to thousands of institutions and researchers in need of greater access to space to further their work and rate of scientific discovery.

Invites the public to participate in Planetary Resources’ asteroid mining mission – Anyone with an interest in space can play a role in opening up the Solar System for human activity.

The whole citizen science thing could really take off. I've used my computer for folding at home. I spent some time IDing galaxies. Finally, and I've been a fan of asteroid mining for a number of years, we might be able to get some use out of all the fanbois out there. It's a way of helping without giving money, but it's really actually helping

Winner

Diverse in Unity

Three promising sci-fi films to see this year.

Hopefully at least one of them will be good and contain some SCI along with the -fi.

Hopefully at least one of them will be good and contain some SCI along with the -fi.

warpus

Sommerswerd asked me to change this

Wow, Europa Descent and Elysium look great

Winner

Diverse in Unity

Wow, Europa Descent and Elysium look great

Yeah. I'll see Elysium if only because I want to see the visualizations of the "space wheel" habitat

As for Europa what'sthesecondwordinthetitle, I wonder whether the film makers considered the radiation levels on the surface and in the general vicinity of Jupiter. Some comments on that article mention the problem. According to wiki, the respective radiation levels on the Galilean moons are:

Io 3600

Europa 540

Ganymede 8

Callisto 0.01

IIRC, ~500 rem is pretty much the lethal dose for an adult human if accrued rapidly. Therefore, a trip to Io will kill you you in little over 3 hours, a stay on Europe will kill you in less than a day, and two earth months on Ganymede will be severely damaging to your long term survival prospects.

The good news is that we probably don't have to worry too much about sterilizing our probes to Europa. The bad news is that unless we can shield our ships effectively on the way in, human landing on the inner three Galilean moons would be bordering on suicide by spaceflight.

PlutonianEmpire

King of the Plutonian Empire

Last night, I posted on facebook a gimped photo where I replaced the moon with two moons of one of my planets', and my father made an off-hand(?) comment about them orbiting each other, although I told him they each had their own circumplanetary orbits.

But then today, it had me wondering, might that actually be a more reasonable/plausible or even more stable if they orbited each other than individually orbiting the terrestrial host planet?

My question is, which of the two situations might have a better chance of happening in the first place and which might actually end up lasting or be stable longer?

But then today, it had me wondering, might that actually be a more reasonable/plausible or even more stable if they orbited each other than individually orbiting the terrestrial host planet?

Spoiler images :

My question is, which of the two situations might have a better chance of happening in the first place and which might actually end up lasting or be stable longer?

Someone has been beating the drum to put a live webcam on the moon for 8 years. It might actually be happening within the next 2

http://brendanloy.tumblr.com/post/51696740231/we-choose-to-put-a-webcam-on-the-moon-in-this-decade

http://brendanloy.tumblr.com/post/51696740231/we-choose-to-put-a-webcam-on-the-moon-in-this-decade

Someone has been beating the drum to put a live webcam on the moon for 8 years. It might actually be happening within the next 2

http://brendanloy.tumblr.com/post/51696740231/we-choose-to-put-a-webcam-on-the-moon-in-this-decade

If this is half as great as it sounds, it will be mine blowing.

The Lunar XPrize is all about getting a camera onto the Moon, too. I keep track of the teams, to see if local one ever pops up that I can root for.

warpus

Sommerswerd asked me to change this

Has this been posted here?

A kickstarter to get a public telescope into orbit for public use. Seems interesting, but the $1 million price tag seems a bit low

A kickstarter to get a public telescope into orbit for public use. Seems interesting, but the $1 million price tag seems a bit low

Winner

Diverse in Unity

My question is, which of the two situations might have a better chance of happening in the first place and which might actually end up lasting or be stable longer?

Whew...

I *think* two moons on separate orbits is a much more likely scenario. The thing is, moons usually don't have their own moons (meta-moons? if nobody had used the term yet I hereby claim it as my own coinage

) because their sphere of influence (SOI) is very small and thus any metamoons would have to orbit pretty close. Then all sorts of other problems develop, such as decaying orbits to to gravitational meddling of the central planet, loss of orbital energy due to tidal stressing, etc. etc. etc. etc. etc.; this is totally beyond my capability to evaluate.

) because their sphere of influence (SOI) is very small and thus any metamoons would have to orbit pretty close. Then all sorts of other problems develop, such as decaying orbits to to gravitational meddling of the central planet, loss of orbital energy due to tidal stressing, etc. etc. etc. etc. etc.; this is totally beyond my capability to evaluate. So, my *guess* is that a) if the moon orbits pretty far from the central planet; b) the moon is fairly large; and c) the metamoon orbits far enough from the parent moon, it can work for SOME TIME. Eventually the metamoon will most likely collide with the parent moon or escape on its own separate orbit.

As for how such a configuration might develop... whew. We are now fairly sure our own moon is a result of a giant impact, probably by a Mars-sized object (Theia) which had originally formed in in one of Sun-Earth Lagrange points. It hit the Earth at an angle and threw out enough debris for it to form a ring and eventually accrete to a planet-sized Moon. Tidal interactions with Earth have then led the orbit of the Moon to expand outwards and circularize to a large degree.

Now, how could a terrestrial planet have two moons? Well, i) there could have been more than one such giant impacts to form multiple moons, or two moons might have formed from one giant impact; ii) the moons might have formed from the same stuff the planet was made; iii) the moons might be captured planetoids (imagine Theia hadn't have hit Earth, but instead entered an elliptical orbit around it. Then we'd have a double-planet).

But if you want to have the moons orbit each other, well, that's something I deem VERY unlikely at least for a terrestrial-sized planets orbiting in the inner solar system. Maybe for a while such a freak configuration might work, but I don't think it can be made stable on the scale of billions of years.

Suggestion - you could have two moons orbiting on the same orbit, the smaller of them being stuck in one of the two stable Lagrange points. In fact, if you want to go all out weird, you can have three such moons in addition to the main moon

PlutonianEmpire

King of the Plutonian Empire

(Don't worry, Winner, I won't forget, I'll answer your post eventually  )

)

http://www.astronomy.com/en/News-Ob...anets are bigger than previously thought.aspx

Ouch. Exoplanet hunting is a helluva headache sometimes, that's for sure.

)

)http://www.astronomy.com/en/News-Ob...anets are bigger than previously thought.aspx

Ouch. Exoplanet hunting is a helluva headache sometimes, that's for sure.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 4

- Views

- 783

- Replies

- 7

- Views

- 1K

- Replies

- 5

- Views

- 4K

- Replies

- 13

- Views

- 2K