You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Today I Learned #4: Somewhere, something incredible is waiting to be known.

- Thread starter Valka D'Ur

- Start date

-

- Tags

- til today i learned

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Always before I've seen the word. Last summer, for the first time, I saw an arrow in it. It was quite surprising. Now I see FedEx but I can see the arrow if I think about it.When you look at the FedEx logo do you see the word FedEx or the arrow?

Narz

keeping it real

Til illuminati actually existed

Berzerker

Deity

according to House smoking 2 cigarettes a day is an effective treatment for inflammatory bowel syndrome

House is a tv drama but I'm sure their writers employ doctors to proofread their scripts

House is a tv drama but I'm sure their writers employ doctors to proofread their scripts

If so, then I doubt that they approved this part o_O. I've seen some blunders in there myself (from the laboratory analysis), so I really would not rely on that :/.

A google check tells me that it's the opposite https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2021.646658/full "In conclusion, smoking seems to be a lifestyle habit which is clearly associated with IBS."

A google check tells me that it's the opposite https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2021.646658/full "In conclusion, smoking seems to be a lifestyle habit which is clearly associated with IBS."

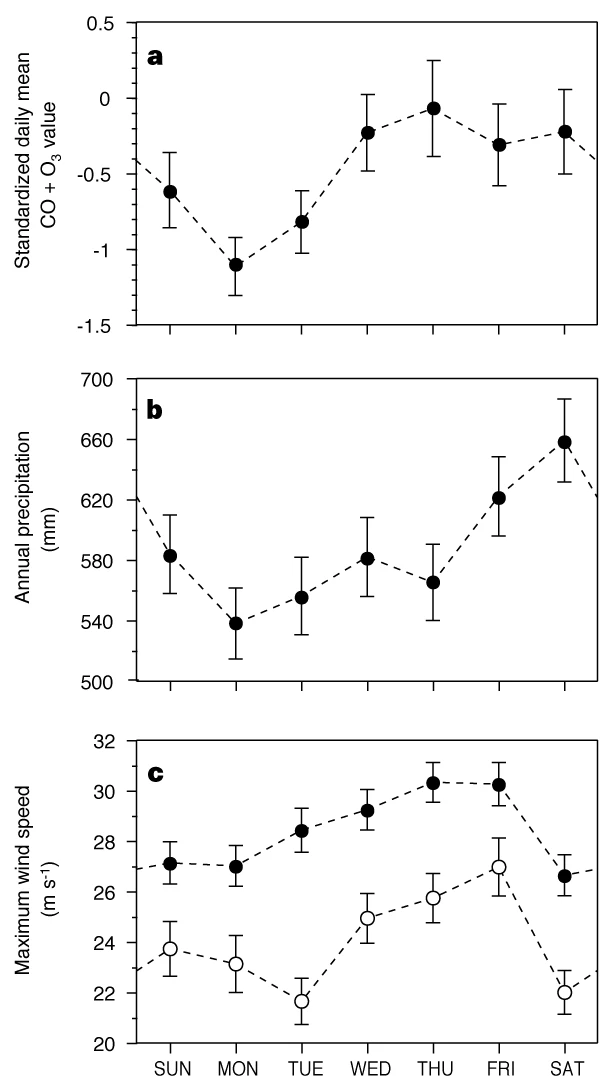

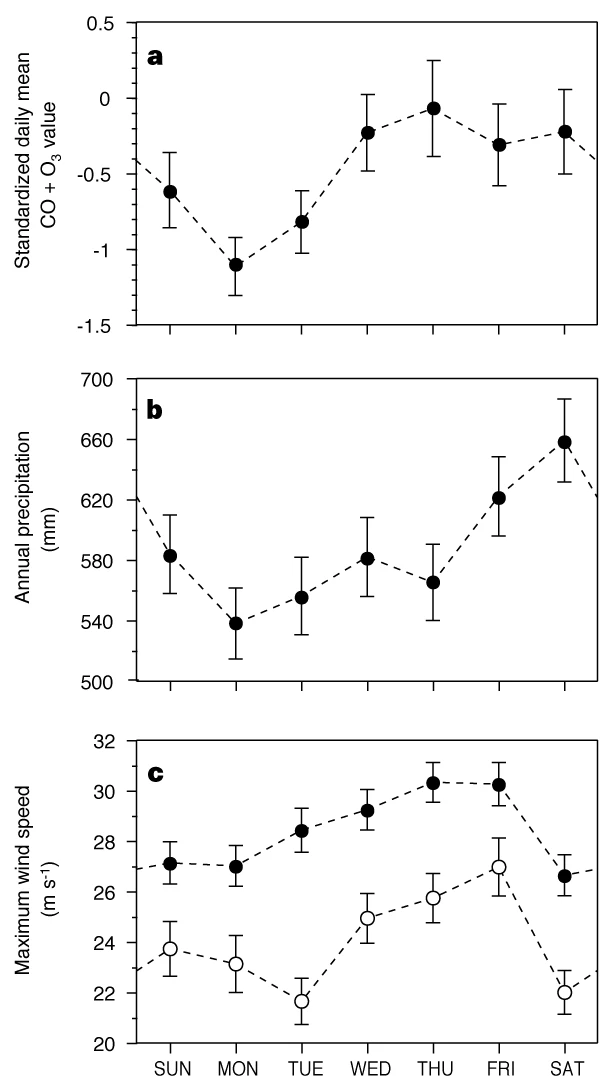

TIL that it really does rain more at the weekends:

Direct human influences on climate have been detected at local scales, such as urban temperature increases and precipitation enhancement, and at global scales. A possible indication of an anthropogenic effect on regional climate is by identification of equivalent weekly cycles in climate and pollution variables. Weekly cycles have been observed in both global surface temperature and local pollution data sets. Here we describe statistical analyses that reveal weekly cycles in three independent regional-scale coastal Atlantic data sets: lower-troposphere pollution, precipitation and tropical cyclones. Three atmospheric monitoring stations record minimum concentrations of ozone and carbon monoxide early in the week, while highest concentrations are observed later in the week. This air-pollution cycle corresponds to observed weekly variability in regional rainfall and tropical cyclones. Specifically, satellite-based precipitation estimates indicate that near-coastal ocean areas receive significantly more precipitation at weekends than on weekdays. Near-coastal tropical cyclones have, on average, significantly weaker surface winds, higher surface pressure and higher frequency at weekends. Although our statistical findings limit the identification of cause–effect relationships, we advance the hypothesis that the thermal influence of pollution-derived aerosols on storms may drive these weekly climate cycles.

Spoiler Legend :

a, Mean values for the summed composite of the standardized species (CO and O3) for Sable island, 1991–95 (the mean of the composite is nonzero owing to the exclusion of missing data pairs); b, total annual precipitation for grid-cells identified in Fig. 1; and c, tropical cyclonic mean maximum wind speed for the ‘long’ (filled circles) data set (1946–96) and ‘short’ (open circles) data set (1970–96).

EgonSpengler

Deity

- Joined

- Jun 26, 2014

- Messages

- 12,260

I loved House, but I seem to remember it being picked as the least-realistic depiction of medicine on tv at the time, in an unscientific poll of health care workers. While I can't remember what other hospital or doctor shows were on at the time, Grey's Anatomy had to have been one of them, and House was judged even less realistic than Grey's.  I can't remember what was picked as the best/most realistic depiction of medicine on tv.

I can't remember what was picked as the best/most realistic depiction of medicine on tv.

I can't remember what was picked as the best/most realistic depiction of medicine on tv.

I can't remember what was picked as the best/most realistic depiction of medicine on tv.Berzerker

Deity

I googled it, the condition smoking might help is ulcerative colitis (UC). I'm sure the show mentioned IBS but so much for that. It didn't help IBS or Crohns and actually made some people worse.

An analysis from 2012Trusted Source took a look at the existing research and found that current smokers are less likely to be diagnosed with UC than people who have never smoked.

Heavier smokers are also less likely than lighter smokers to develop UC. And former smokers develop the condition later than people who have never smoked.

Also, current smokers with UC tend to have a milder form of the condition than former smokers and people who have never smoked.

Researchers think this may be due to nicotine’s ability to stop the release of inflammation-producing cells in the digestive tract. This anti-inflammatory action may, in turn, stop the immune system from mistakenly attacking good cells in the intestines.

https://www.healthline.com/health/ulcerative-colitis-and-smoking#research

About a decade ago I pulled a rib cage muscle and used Super Blue Emu Stuff cream. Big mistake. The cream was very effective but it got into my lungs or internal organs and not just ruined by taste buds but made some things taste bad. I tried licorice and other edibles like mints but to no avail. Now a few years earlier I had quit smoking but as a last resort I bought a pack of smokes and it worked. I dont remember if my taste buds returned to "normal" but the improvement was life changing and I quit smoking a few weeks later to see if the issue was resolved and it had. Maybe the Emu cream worked its way out of my system or it was the tobacco.

An analysis from 2012Trusted Source took a look at the existing research and found that current smokers are less likely to be diagnosed with UC than people who have never smoked.

Heavier smokers are also less likely than lighter smokers to develop UC. And former smokers develop the condition later than people who have never smoked.

Also, current smokers with UC tend to have a milder form of the condition than former smokers and people who have never smoked.

Researchers think this may be due to nicotine’s ability to stop the release of inflammation-producing cells in the digestive tract. This anti-inflammatory action may, in turn, stop the immune system from mistakenly attacking good cells in the intestines.

https://www.healthline.com/health/ulcerative-colitis-and-smoking#research

About a decade ago I pulled a rib cage muscle and used Super Blue Emu Stuff cream. Big mistake. The cream was very effective but it got into my lungs or internal organs and not just ruined by taste buds but made some things taste bad. I tried licorice and other edibles like mints but to no avail. Now a few years earlier I had quit smoking but as a last resort I bought a pack of smokes and it worked. I dont remember if my taste buds returned to "normal" but the improvement was life changing and I quit smoking a few weeks later to see if the issue was resolved and it had. Maybe the Emu cream worked its way out of my system or it was the tobacco.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Camel_Corps

It seems the US was experimenting with Camels in its army. The project got abandoned due to the civil war.

It seems the US was experimenting with Camels in its army. The project got abandoned due to the civil war.

EgonSpengler

Deity

- Joined

- Jun 26, 2014

- Messages

- 12,260

I'm watching an interview with Maria Franz and she pronounces Euzen "yoo-seen." Just looking at the word, I thought it might be German - "oy-sun", maybe - but no, she says the word was taken from Ancient Greek, and isn't sure how it would have been pronounced. She pronounces Songleikr almost like "song-like-er/-ir." The kr sound at the end is very quick, the way she says it, so fast it almost sounds like "-it" to me. "Song-like-ear" would be elongating the sound too much.

I also listened to a podcast interview with Katheryn Winnick, and wow, does she have a strong accent. She's from Toronto (Etobicoke, specifically, if you know that city). I've never heard her speaking in her natural voice before.

I also listened to a podcast interview with Katheryn Winnick, and wow, does she have a strong accent. She's from Toronto (Etobicoke, specifically, if you know that city). I've never heard her speaking in her natural voice before.

Last edited:

In Modern Greek they've usually changed to ‘ia’:

But some archaicists deliberately use older forms:

In Classical (Attic) Greek it would've been ‘eu’. I.e., for an English-speaker, the e as in met and the u as an ‘oo’ sound but short instead of long.

I suppose that Maria Franz pronouncing it ‘yoo-zen’ actually comes from the English pronounciation (see Euthanasia/Youthanasia), but if they're a German-Danish-Swedish band then it's a bit baffling.

*rolls eyes at humanity*

Zeus → Dias

Basileus → Vasilias

Basileus → Vasilias

But some archaicists deliberately use older forms:

Vasilefs

In Classical (Attic) Greek it would've been ‘eu’. I.e., for an English-speaker, the e as in met and the u as an ‘oo’ sound but short instead of long.

I suppose that Maria Franz pronouncing it ‘yoo-zen’ actually comes from the English pronounciation (see Euthanasia/Youthanasia), but if they're a German-Danish-Swedish band then it's a bit baffling.

*rolls eyes at humanity*

Snowygerry

Deity

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Camel_Corps

It seems the US was experimenting with Camels in its army. The project got abandoned due to the civil war.

https://www.bol.com/be/nl/p/blauwbloezen-25-blauwen-en-bulten/1001004005166241/

TIL: WORD ON THE STREET

From Early Sci-Fi to The Online Nuisances Of Today

[Bot]

TESLA CEO Elon Musk has placed his acquisition of Twitter “on hold” until the social media giant clarifies how many of its accounts are autonomous “bots,” or fake accounts designed to mimic human behavior. The wrangling over the bot issue has led many to wonder whether Mr. Musk is trying to drive down the price of the company or walk away from his offer.

On Twitter, many “bots” are entirely benign: They can be set up to automate various tasks, such as posting top news stories. There are even bots that promote self-care and combat online bullying. But the bots Mr. Musk is concerned about engage in deceptive or harmful activities, such as spreading unwanted spam and misinformation, sometimes with the goal of inciting violence or interfering with elections.

The bad reputation of bots isn’t surprising, considering the checkered legacy of the term from which “bot” derives: “robot.” Last year marked the 100th anniversary of the public debut of “robot,” a word introduced by the Czech writer Karel Čapek in his science-fiction play “R.U.R.,” short for “Rossum’s Universal Robots.” The play, which premiered in Prague on Jan. 25, 1921, tells the story of a factory that creates artificial workers or “roboti.” These mechanical workers eventually start a rebellion that leads to the extinction of the human race.

Čapek’s coinage was based on a pre-existing Czech word, “robota,” which could mean “forced labor” or “drudgery,” in turn from a Slavic root, “rabu,” meaning “slave.” While the play was written in Czech, Čapek’s original publication in 1920 provided the subtitle of “Rossum’s Universal Robots” in English. The expression spread quickly when the play’s English translation made its debut in 1922. The New York Times ex- plained the plot: “Later the robots organize and wage a war against the people, during which the robots destroy all human beings.”

The Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction, an online resource edited by Jesse Sheidlower, documents the evolution of “robot” and its many lexical spinoffs. As robotic characters became regular features in American science fiction, Isaac Asimov did much to popularize the term in his stories from the 1940s collected in “I, Robot.” Asimov codified the “Three Laws of Robotics” governing the actions of robots in his fiction, which also features the protagonist Susan Calvin, a “robopsychologist.” (That is a human psychologist who studies robots, not a robotic psychologist.)

Other science-fiction writers got in on the robo-coinages. A. E. van Vogt wrote of “roboplanes” in 1945, and Poul Anderson offered “robocomputers” in 1949. “Robocop,” for a robotic police officer, dates to a 1957 Harlan Ellison story, three decades before the dystopian movie of the same name.

Clipping “robot” from the other direction, “bot” made its earliest known appearance in Richard C. Meredith’s story “We All Died at Breakaway Station,” published in the magazine Amazing Stories in 1969. Meredith wrote of “’bots” (with an apostrophe) as a kind of nickname, but “bot” soon became a popular shortening— sometimes working as a suffix, as in “fembot” for a robot with a feminine appearance (appearing in a 1976 review of the TV show “The Bionic Woman”).

JAMES YANG

Real-world robotics introduced such terms as “nanobot” for a very small self-propelled machine. Automated computer programs for specific tasks got the “bot” label starting around 1990, with programs designed to simulate conversations called “chatterbots” or “chatbots.” Malicious “spambots” soon became the bane of email, online forums, and eventually Twitter. Spammers may employ a “botnet,” or a network of “zombie” computers infected with malicious software. These days, bots designed with ill intent far outnumber innocuous ones—though perhaps in the future good bots can be organized to combat the bad bots.

From Early Sci-Fi to The Online Nuisances Of Today

[Bot]

TESLA CEO Elon Musk has placed his acquisition of Twitter “on hold” until the social media giant clarifies how many of its accounts are autonomous “bots,” or fake accounts designed to mimic human behavior. The wrangling over the bot issue has led many to wonder whether Mr. Musk is trying to drive down the price of the company or walk away from his offer.

On Twitter, many “bots” are entirely benign: They can be set up to automate various tasks, such as posting top news stories. There are even bots that promote self-care and combat online bullying. But the bots Mr. Musk is concerned about engage in deceptive or harmful activities, such as spreading unwanted spam and misinformation, sometimes with the goal of inciting violence or interfering with elections.

The bad reputation of bots isn’t surprising, considering the checkered legacy of the term from which “bot” derives: “robot.” Last year marked the 100th anniversary of the public debut of “robot,” a word introduced by the Czech writer Karel Čapek in his science-fiction play “R.U.R.,” short for “Rossum’s Universal Robots.” The play, which premiered in Prague on Jan. 25, 1921, tells the story of a factory that creates artificial workers or “roboti.” These mechanical workers eventually start a rebellion that leads to the extinction of the human race.

Čapek’s coinage was based on a pre-existing Czech word, “robota,” which could mean “forced labor” or “drudgery,” in turn from a Slavic root, “rabu,” meaning “slave.” While the play was written in Czech, Čapek’s original publication in 1920 provided the subtitle of “Rossum’s Universal Robots” in English. The expression spread quickly when the play’s English translation made its debut in 1922. The New York Times ex- plained the plot: “Later the robots organize and wage a war against the people, during which the robots destroy all human beings.”

The Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction, an online resource edited by Jesse Sheidlower, documents the evolution of “robot” and its many lexical spinoffs. As robotic characters became regular features in American science fiction, Isaac Asimov did much to popularize the term in his stories from the 1940s collected in “I, Robot.” Asimov codified the “Three Laws of Robotics” governing the actions of robots in his fiction, which also features the protagonist Susan Calvin, a “robopsychologist.” (That is a human psychologist who studies robots, not a robotic psychologist.)

Other science-fiction writers got in on the robo-coinages. A. E. van Vogt wrote of “roboplanes” in 1945, and Poul Anderson offered “robocomputers” in 1949. “Robocop,” for a robotic police officer, dates to a 1957 Harlan Ellison story, three decades before the dystopian movie of the same name.

Clipping “robot” from the other direction, “bot” made its earliest known appearance in Richard C. Meredith’s story “We All Died at Breakaway Station,” published in the magazine Amazing Stories in 1969. Meredith wrote of “’bots” (with an apostrophe) as a kind of nickname, but “bot” soon became a popular shortening— sometimes working as a suffix, as in “fembot” for a robot with a feminine appearance (appearing in a 1976 review of the TV show “The Bionic Woman”).

JAMES YANG

Real-world robotics introduced such terms as “nanobot” for a very small self-propelled machine. Automated computer programs for specific tasks got the “bot” label starting around 1990, with programs designed to simulate conversations called “chatterbots” or “chatbots.” Malicious “spambots” soon became the bane of email, online forums, and eventually Twitter. Spammers may employ a “botnet,” or a network of “zombie” computers infected with malicious software. These days, bots designed with ill intent far outnumber innocuous ones—though perhaps in the future good bots can be organized to combat the bad bots.

Last edited:

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 0

- Views

- 2K

- Sticky

- Replies

- 9

- Views

- 6K

- Replies

- 2

- Views

- 571