Traitorfish

The Tighnahulish Kid

"Economic" and "political" aren't concretely distinct spheres of activity. The economic is always, necessarily, political, and the political is always, necessarily, economic. The state is an economic entity and private companies are political entities, each as much as the other.In communism they're elected, or at least communally decided. That's the flaw with capitalism - political entities are democratically elected while economic entities (and wealthy people) arise as a course of "might makes right" in a slightly more complicated system.

Regardless, I gather from your statement that you are defining the state as not only the political component, but the entire entity, which includes the economic component.

I don't even know what you're saying, here. Just sounds like you're regurgitating the old, discredited Orthodox Marxist logic of "historical progress", but stripped of even the halfway-radical class politics it implied. A fancy way of saying "don't rock the boat".My point is that human social development lead to the evolution of states. I would venture to guess that your assertion is that each social system evolution came as a result of predators attempting to maximize predation under an adapting order, and perhaps in spite of workers (and their demands for equity) instead of for them. Perhaps I am too much of an optimist and/or you too much of a pessimist, but I perceive a great attribution of such change to be separate from the people involved, with no intent (i.e. some mystical concept of social or cultural evolution, rather than a group of people).

How?I also believe that the advent of democracy has changed a multitude of factors as well. Currently, the wealthy will have a great level of influence, affecting many policies across the board. However, to an unprecedented extent, the people now have a not-insignificant level of influence as well. Capitalism can indeed be "reformed away" to be less predatory on the workers. At least until the people collect sufficient education, awareness, and power to truly change things.

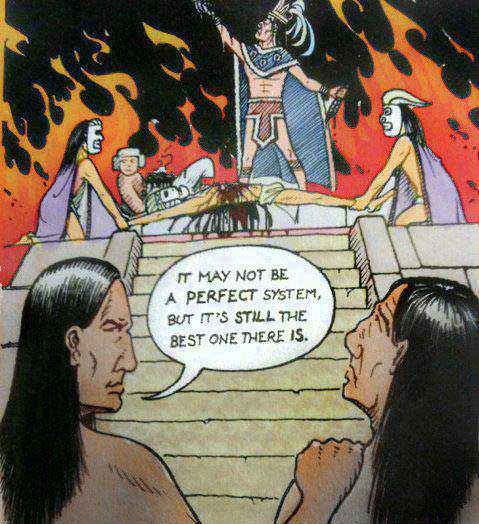

The shortfall of capitalism is that it is capitalism. A system dominated by the accumulation of dead labour, a system in which living beings strive to fill the needs of unliving capital. That can't be voted away, that can't be rectified by redistributing the proceeds. What you propose is inviting workers to participate in the management of their own exploitation, to serve as the officers of the expropriation of their own labour, to actively participate in the perpetuation of the dictatorship of capital- and you call that progress?We would have to look at capitalism's shortfalls to address that. The way I see it, there are only two outcomes that fundamentally flaw capitalism.

One is that the residual fruits of workers' labours are remitted to the capitalists. I say residual since workers do get some fruits of their labour (wages), but this point is meant to also encapsulate the illegitimacy of wealth. That is, that capitalists can earn economic benefits by merely owning wealth, rather than performing actions deserving of such benefits. An argument made for the idea that they had performed actions in the past leading to their wealth is flawed from both an inheritance perspective (where does this wealth go when they die?) and from the circular argument that presupposes that earnings made under such a system are indeed legitimate.

The second is that the capitalists have total economic control. Even if all workers were to be paid handsome wages, it would still be the wealth-owners who would make all the decisions and have all the control over how such wealth would be handled and distributed. Workers would still have to choose their "master" to provide wages necessary for living, while the masters control all aspects (to the extent they wish).

A democratically-elected government has a higher degree of influence from the workers themselves, and can align the system more to the workers' goals. The first flaw can be addressed through taxation schemes that "redistribute" the wealth to some minor degree. The second flaw can be addressed by providing the people more power, since they now indirectly control this political government that can influence the system and aspects thereof.

Just because political reform has been slow or ineffective in the past century doesn't mean that it will continue to be just as slow. I would expect an exponential increase in effectiveness over time as technological advances increase education and social communication and commentary.

The call for a decent wage is an apology for the essential indecency of the wage-system itself.

Capital is a social relation. All property-forms are social relations. The legal abstraction f property, property as a static and persistent thing, is a collective fiction we entertain to describe and regulate those social relations. The reality of property consists in real social practice, in what people actually do. In capitalism, that means wage-labour, the need of both capital and labour to engage in wage-relations in order to reproduce themselves. That is neither a comprehensive nor exhaustive description of capitalism, but nobody ever said it had to be: it is enough that it tells why "capitalism" is different than "not-capitalism".I don't think wages are a defining element of capitalism. Private property rights are. Here's why: It's already in the name, being the 'capital' of "capitalism". Capitalism is about free ownership of capital, free in the sense of no legal impairments to owning capital due to matters of birth, like would be more or less the case in Medieval Europe for example. It's - as you mentioned - also about getting profit, or at the very least, avoiding losses.

No wage-system, no capitalism, just a lot of shopkeepers and small farmers, selling a greater or lesser part of their produce, and that pre-dates even the earliest estimations of the genesis of capitalism by a few centuries at least.

Capital is not a trans-historical category. Humans have not always organised themselves on such a basis; what makes you think we must continue to do so?It's easy and understandable to think that the ownership of capital to extract profits is somehow parasitic in the same way anarcho-capitalists would consider the state it to be. That - I know - is your position. However, eliminating capitalism would simply impair the ability of capital to be mobilized, made and used to least of societal loss possible, as is the experience of states that do not allow for Capitalism to fully express itself (i.e. the Soviet Union, 18th century France and most Third world countries). Entrepreneurs can only raise capital by having "skin in the game" (taking significant personal risks in doing so). Now, my position on Capitalism of course comes quite close to Libertarianism, if Libertarians would not support that outright. But the primary problems of capitalism consist primarily in the form of renter Capitalism most infamously represented by the sorry state of the financial sector, which is able to socialise losses but capitalise on profits.