You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Mohammed - Prophet of Peace

- Thread starter Aroddo

- Start date

Oh, sure. Then I guess we can just rephrase the question using 'hard agnositicism' as what is being questioned about.

Traitorfish

The Tighnahulish Kid

Are you sure? From what I've heard, he usually talks in terms of "weak" and "strong" atheism, rather than "agnosticism" and "atheism".I used it the way Dawkins used it...

kochman

Deity

- Joined

- Jun 8, 2009

- Messages

- 10,818

I love when we start nitpicking...

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/rel...m-6.9-out-7-sure-that-God-does-not-exist.html

And, he said something like, on a scale of 7, he is 6.9 sure there is no god.

Also...

Anyhow, point is, atheism is hardly "flourishing"... let's not get hung up on words... are the two even mutually exclusive?

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/rel...m-6.9-out-7-sure-that-God-does-not-exist.html

And, he said something like, on a scale of 7, he is 6.9 sure there is no god.

Also...

The philosopher Sir Anthony Kenny, who chaired the discussion, interjected: Why dont you call yourself an agnostic? Prof Dawkins answered that he did.

Anyhow, point is, atheism is hardly "flourishing"... let's not get hung up on words... are the two even mutually exclusive?

Traitorfish

The Tighnahulish Kid

Why shouldn't we, given that you find yourself so hung on the word "flourishing"?

Traitorfish

The Tighnahulish Kid

Could you explain why?

General Pilates

Warlord

Bit false. Invading muslim armies massacred, raped, took slaves and killed just like all the other invading armies of the time. One of the more famous one (or atleast the one I remember) was the total destruction of Carthago in North Africa.

What destruction? The Arabs found a city that was in ruins except for a small garrison fort and a few pathetic squatters living among grandiose ruins. Carthago was all but dead when it fell in 698.

mmmmmmmmmmmwhatWhat destruction? The Arabs found a city that was in ruins except for a small garrison fort and a few pathetic squatters living among grandiose ruins. Carthago was all but dead when it fell in 698.

innonimatu

the resident Cassandra

- Joined

- Dec 4, 2006

- Messages

- 15,374

Finally this is drifting to something a little interesting again! What did happen when the arabs invaded byzantine North Africa? That area seems to have descended into backwater status around the time.

kochman

Deity

- Joined

- Jun 8, 2009

- Messages

- 10,818

What destruction? The Arabs found a city that was in ruins except for a small garrison fort and a few pathetic squatters living among grandiose ruins. Carthago was all but dead when it fell in 698.

How about Alexandria, where the Great Library was? Etc, etc, etc...

Huayna Capac357

Deity

The Great Library had been gone for centuries by the time that the Arabs arrived.

General Pilates

Warlord

mmmmmmmmmmmwhat

Are you suggesting that Carthago was still a metropolis in 698? If so, please expand on your answer; I'm curious about this sort of thing.

Finally this is drifting to something a little interesting again! What did happen when the arabs invaded byzantine North Africa? That area seems to have descended into backwater status around the time.

Dachs will probably slaughter my interpretation, but as far as I know, Byzantine North Africa as a whole was only, in reality, a few secure naval bases along the coast (Melilla, Carthago). Most of the inland areas had been taken over by Berbers who had taken advantage of the fact that the Byzantines were neglecting the area.

Lot of debate about that. The eminent Walter Kaegi has recently published an overview work on the invasion - like, in the last year - but his interpretation has not exactly met with universal approval. You should check it out - preferably by borrowing it from a library, of course, because it's freaking expensive.Finally this is drifting to something a little interesting again! What did happen when the arabs invaded byzantine North Africa? That area seems to have descended into backwater status around the time.

Karchedon was certainly not reduced to "a small garrison fort and a few pathetic squatters living amongst grandiose ruins" by the late seventh century. While the region had certainly declined from its high point of prosperity in the late fourth century due to the collapse of the trade spine with Rome, it was not a precipitous decline. ARS (African Red Slip pottery, made chiefly in Karchedon and the environs) was still produced, and still appeared widely in the Mediterranean up to about the same time as the Muslim conquest. We've tended to track the decline of Mediterranean trade chiefly through the decreasing amounts of ARS visible in period archaeological sites; the disappearance of such pottery from all but coastal Iberia, for instance, in the fifth and sixth centuries, is a good barometer of how disconnected the peninsula was becoming from the remnant of the Mediterranean trading economy. Anyway, point is that ARS was still being made in what appear to have been significant numbers through the seventh century.

In terms of population, well, we're not really sure, but as you know we're never really all that sure about populations in the relevant period anyway. There's clear signs of habitation throughout most of the city. North African political life was relatively vibrant and there was a great deal of discourse about religious controversy with the central authorities in Constantinople. The result of the Battle of Yarmouk, for instance, was frequently connected to the Emperors' meddling with monotheletism and monoenergism, both of which were regarded as pretty much heretical. Konstas II's promulgation of the Type in particular seems to have ruffled a lot of feathers and instigated some persecution.

Africa was still valuable to anybody who would choose to hold it. A century before - well, slightly less - Herakleios and his father had waged a civil war from Africa against the central authorities and won; somewhat later, the exarchos Yennadios had attempted to resist Konstas II and held his own for quite some time before the Emperor moved west, established his residence at Syrakousai, and forced Africa's submission.

Nevertheless, Africa's military resources were somewhat scarce, made slightly more so by the region's low overall population and recruitment base. They also had low renewability, forcing the exarchal authorities to rely on recruits from Mauri and other tribal groups to make up losses suffered in battle. Reinforcements from Anatolia and the Aegean were effectively out of the question, especially considering the Byzantine fleet's parlous situation in the second half of the seventh century, weakened by defeats like the Battle of the Masts. It was considerably isolated from the rest of the Byzantine state. Even if it had not been, the region was rapidly becoming a hotbed of opposition to certain key planks of imperial policy, planks that would not really change until after the Seven Revolutions. It may have been deemed too much trouble to save.

With all that in mind, it is easy to understand the collapse of Byzantine power in the region. An initial battle permitted the Muslims to establish a foothold in the region at Qayrawan, which badly destabilized what was left of Byzantine government and drove a wedge between the Mauri and the imperial authorities; by the late seventh century, the ultimate military result just had to be played out.

On the subject of atrocities: I wasn't aware that the capture of Karchedon was particularly noteworthy one way or the other. I haven't read anything about massacres outside the norm during the conquest of Byzantine Africa, and neither have I read anything about unusually clement behavior on the part of the conquerors.

innonimatu

the resident Cassandra

- Joined

- Dec 4, 2006

- Messages

- 15,374

Thanks, that was very interesting. It's not much information, but one finds so little about that comparatively neglected piece of the Mediterranean. The book you meant is "Muslim Expansion and Byzantine Collapse in North Africa"? Too bad I'm unlikely to find it in libraries here. I guessed that Africa must have remained important until the 7th century given that it had just supported Heraclius' rebellion, but that it wasn't a good recruitment base comes as a surprise. Perhaps that helps explain why the empire also failed to hold the south of the Iberian Peninsula, which seemed well worth holding (the Arabs, after all, managed it for a long time): they lacked manpower form their nearest main in Africa, and elsewhere it was tied up in different conflicts?

It still seems amazing how fast the arabs seized the provinces of the empire piece by piece, especially as the arabs themselves must not have been that numerous. Can the explanation be as simple as that old "nomad advantage" of using a large proportion of their male population as warriors?

It still seems amazing how fast the arabs seized the provinces of the empire piece by piece, especially as the arabs themselves must not have been that numerous. Can the explanation be as simple as that old "nomad advantage" of using a large proportion of their male population as warriors?

_random_

Jewel Runner

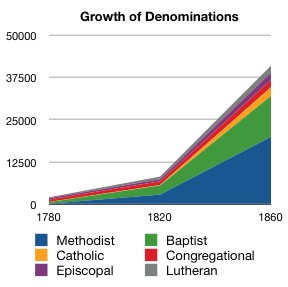

Admittedly, never quite to this extent, but religiousity has declined and spiked:When historically did atheism flourish besides now?

(That's for the United States FYI)

aronnax

Let your spirit be free

Lot of debate about that. The eminent Walter Kaegi has recently published an overview work on the invasion - like, in the last year - but his interpretation has not exactly met with universal approval. You should check it out - preferably by borrowing it from a library, of course, because it's freaking expensive.

Karchedon was certainly not reduced to "a small garrison fort and a few pathetic squatters living amongst grandiose ruins" by the late seventh century...

You mentioned that it wasn't met with universal approval. What did the opposition say?

Similar threads

- Replies

- 16

- Views

- 3K

- Replies

- 26

- Views

- 5K

- Replies

- 62

- Views

- 7K

- Replies

- 93

- Views

- 5K