In June 2020, he set out to test his hypothesis. Barham, Christian Hall, a fellow rhinologist, and Mohamed Taha, an otolaryngologist and research fellow, did a retrospective study — looking at 100 patients who earlier had tested positive for the coronavirus. They used the same test Barham had given to his friend and his wife: four small strips of paper placed on the tongue, one at a time, after which the patient rated the intensity of flavor from 1 to 10 (mildly bitter to intensely bitter, for example).

None of the 100 patients tested was classified as a supertaster. Seventy-nine patients had mild-to-moderate coronavirus symptoms and they were classified as tasters. And 21, who had been seriously ill and required hospitalization, were classified as nontasters. The study’s findings

were published in August 2020 in the International Forum of Allergy & Rhinology.

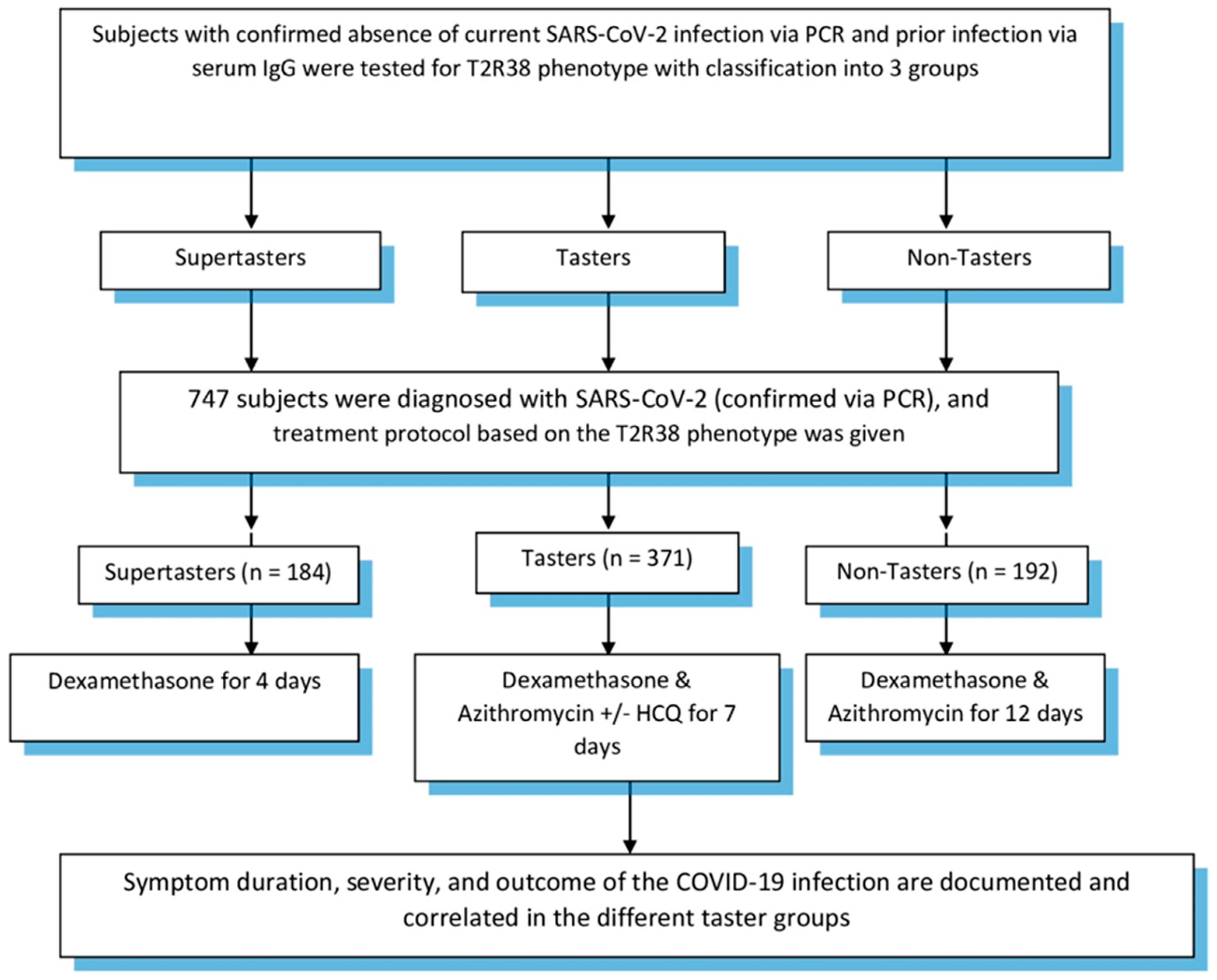

These results were promising but because loss of taste and smell were common symptoms of the coronavirus, Barham and his team set out to create a study that would be able to account for those losses. As they put it in their study, it wasn’t clear whether a person’s supertaster status predicted the severity of covid-19 or was a consequence of infection severity. They had to test people before they got covid-19, and then again, afterward.

The study tested people for the absence of both prior and current coronavirus-related infection. They then took the paper-strip taste test, and a subgroup also supplied spit samples for genetic testing, which provides greater accuracy.

From July 1 through Sept. 30, 2020, they followed 1,935 patients and health-care workers who had been exposed to the coronavirus but had neither a previous nor current infection. Each was given the paper-strip taste test, and a subgroup also supplied spit samples. About half were classified as tasters, a quarter as nontasters, and a quarter as supertasters. During the follow-up period, 266 of the 1,935 people tested positive for the coronavirus. Nontasters, the researchers found in the

study published last month, were far more likely to contract the disease and for their symptoms to last longer: an average of 23.5 days — compared to five days for supertasters and 13.5 days for tasters.

Nontasters were also far more likely to be hospitalized. Of the 55 study participants hospitalized, 47 (85.5 percent) were nontasters. Of the supertasters who tested positive, none needed to be hospitalized. These results indicated the accuracy rate for predicting severity of the disease based on a person’s taster status was 94.2 percent. Barham says the 5.8 percent discrepancy can be explained by the age of some of the participants. The mean age of tasters requiring hospitalization was 74 (the mean age of all participants was 45.5.), and supertasters’ ability to taste

diminishes over time.